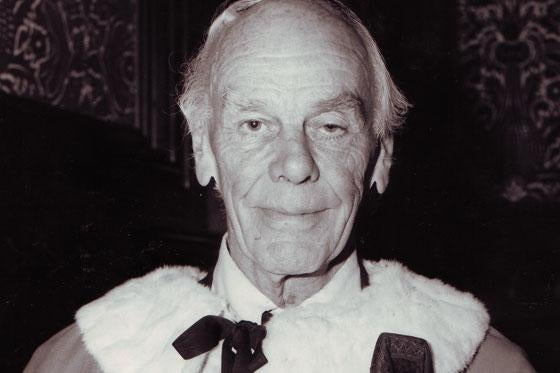

Lady Thatcher and Charles Moore led figures from politics and the media today paying tribute to Lord Deedes, the former Daily Telegraph editor and Conservative cabinet minister.

Lord Deedes, universally known as Bill, was remembered as a soldier, politician and journalist.

His journalistic career spanned nearly 80 years – joining the Morning Post in 1931 and still writing a weekly column for the Telegraph when he died in August at the age of 94.

Bill Deedes served with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps during the Second World War – the only officer in his company to come through physically unscathed from D-Day to VE Day. In April 1945, he won the Military Cross for rescuing injured men under heavy fire on a bridge over the Twente Canal.

He was Conservative MP for Ashford, Kent, for 25 years and a cabinet minister from 1962 to 1964. He had left politics and returned to journalism as editor of the Telegraph by the time Lady Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979.

Carol Thatcher, who accompanied her mother to the memorial service at the Guards Chapel, Wellington Barracks, said afterwards: “She was terribly fond of Bill. Bill gave a wonderful address at Denis’s memorial here in the Guards Chapel three years ago.”

Charles Moore, a former editor of The Daily Telegraph, who gave the address, said when Lord Deedes became a journalist, Ramsay MacDonald was Prime Minister. When he died, it was Gordon Brown. He reported on both.

“Winston Churchill made him a minister. Harold Macmillan put him in the Cabinet. Margaret Thatcher made him a peer. Denis Thatcher made him have another pink gin at the 19th hole,” he said.

“Bill covered the abdication of King Edward VIII, and he travelled, in his campaign to rid the world of landmines, with Diana, Princess of Wales. He saw Africa with Evelyn Waugh in 1935, and with her more than 60 years later.”

In 1935, the young Deedes was sent by The Morning Post to cover Mussolini’s imminent attack on Abyssinia. In Addis Ababa he came across Waugh, employed on the same mission by the Daily Mail.

Deedes was equipped with a quarter of a ton of luggage, which included a cedar wood chest lined with zinc to repel ants and all manner of equestrian equipment – even though he did not ride.

He had three tropical outfits from Austin Reed, although Addis Ababa, 8,000ft above sea level, was cold and damp, and he wore the tweed suit in which he left London.

He was immortalised as William Boot who used cleft sticks to send messages by native runners in Waugh’s novel Scoop – an extract of which was read at the service by Lord Deedes’s son, Jeremy, a former editorial executive at the Telegraph.

After being replaced by Sir Max Hastings as editor of the Telegraph in 1986, Lord Deedes continued to write for the paper.

He went on more than 50 assignments for the Telegraph to the trouble spots of the world to Iraq, Sudan, Angola, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone and Bosnia.

When he was 87, he suffered a stroke on a helicopter covering the Indian earthquake. He attributed this to the lack of whisky.

Moore said: “For those of us in the office, it was wonderful to see such a professional at work. Bill knew what a story was, and how to tell it.

“He had the great journalistic skill of recycling material, often squirreled away for decades.

“He did what was asked, to length, on time, every time. He reckoned he was doing badly if he did not manage 1,000 words in 100 minutes. He never disappointed his editor,” Mr Moore said.

Lord Deedes was known at Telegraph editorial conferences for a “creative mangling” of well-known metaphors.

“Carrington carries a lot of ice,” he would say, or “We’ll burn that bridge when we come to it.”

Moore said: “My favourite, so suitable for the sulphurous intrigue of the Wilson/Callaghan years, was ‘I smell the finger of the Labour Party in this one’.

“Much as he loved the company of his colleagues, Bill never forgot that he was writing for millions of people.

“His writing style united two qualities which rarely go together – plainness and charm. It never showed off, but it did delight.

“The readers loved his gentle, unpolitical conservatism, his embodiment of an idea of England. He was on their side rather than that of the powerful. He was the readers’ best friend.

“In old age, he travelled relentlessly to scenes of war and famine, reporting the distress he found. Yet his articles retained an easy tone of genial conversation. ‘You have to give people hope,’ he would say. ‘People are not motivated to act if all they read about is despair’.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog