Press Gazette has spoken to two journalists who played a crucial role in the exposure of Britain’s biggest medical scandal.

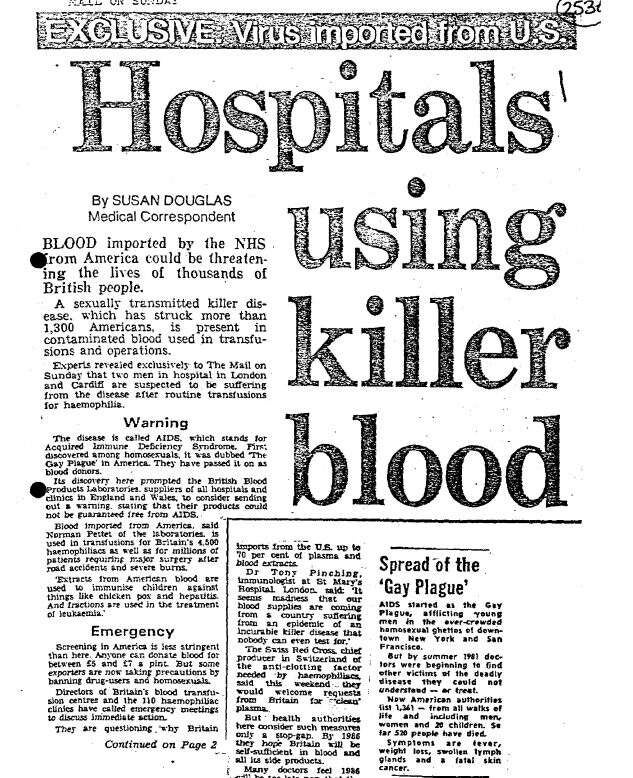

Sue Douglas was a 26-year-old health reporter when she risked her career with the May 1983 front-page story for the Mail on Sunday that first brought the scandal to national attention.

And Sunday Times political editor Caroline Wheeler has spoken of her 24 years campaigning on the issue and the crucial role her paper played in finally securing the public inquiry, which reported last month and held the medical establishment to account on behalf of the estimated 30,000 victims (around 3,000 of whom have lost their lives).

Over the last 40 years there were campaigns by The Sunday Times (in the 1980s) and the Daily Express (in the late 2010s) and widespread coverage elsewhere in the media. But these two journalists did as much as anyone to ensure the UK Government finally took responsibility for an avoidable and catastrophic medical disaster.

Douglas concealed her identity in first conversations with whistleblower

Douglas (pictured above, left), told Press Gazette how concealed the fact she was a journalist to help secure her initial expose and why she fears the same story might not get told today.

Concerns about infected human blood plasma being imported to the UK were circulating in specialist medical circles in early 1983 but had yet to become a major story.

Douglas joined the Mail on Sunday from specialist doctors’ magazine MIMS in 1982 after studying physiology and biochemistry at university. The newly-launched Mail on Sunday was then edited by Stewart Steven who was keen to establish the title with some hard-hitting investigations.

Fellow medical journalist Lorraine Fraser supplied Douglas with medical papers on the issue from The Lancet and put her in touch with a potential whistleblower, the head of haematology at a major hospital. Douglas posed as a haematologist herself to discuss concerns about infected blood with the source.

She said: “At that stage I thought that it was ill-advised to scare the the horses. So I said that I was really interested in the issue, I’d heard him speaking at this conference and could he and I discuss it further? I didn’t tell him I was a journalist.

“We talked a lot about the gathering concerns in the scientific community about the contamination of blood that we were using to save lives.”

Douglas subsequently explored the issue further with colleagues on the Mail on Sunday, speaking to more political and medical sources, and discovered there was a possible solution, sourcing heat-treated blood at greater expense.

Before running the story Douglas called her contact to explain that she was in fact a journalist.

“I read him the whole piece and there was a long silence. I said, ‘so is everything correct?’

“‘Yes.’

“I said, ‘are you happy that I run it?’

“And obviously he wasn’t happy because he was going to be in some considerable danger for his own job.”

But the source agreed to publication as long as his anonymity was protected.

The story, under the headline “Hospitals using killer blood”, revealed that blood imported to the UK from America was infected by the then little-known AIDS virus putting thousands of lives at risk. It revealed that two Britons had already been infected with the then-deadly virus as a result of receiving blood transfusions as part of their treatment for haemophilia.

Mail on Sunday dubbed ‘sensational’ and ‘inaccurate’

The Mail on Sunday faced a backlash from doctors who feared its story would prompt a panic and lead haemophiliacs to avoid blood plasma treatment.

Dr Peter Jones, director of Newcastle Haemophilia Centre, made a formal complaint to the Press Council (the body then overseeing press standards) over the Mail on Sunday report describing it as “sensational and highly exaggerated” and “neither objective or accurate”. He also accused Douglas of “appalling ineptitude”.

The complaint was upheld with the Press Council ruling that the paper used “used extravagant and alarmist terms not justified by the evidence”. Douglas believes the sensationalist front page headline was justified given the seriousness of the story.

“I was frightened, you know, 25 or 26 years old and the editor called me and said the Press Council are calling for me to sack you because you’ve been irresponsible.”

Other titles were initially reluctant to follow the story up because of the complaints and subsequent Press Council ruling. But Douglas recalls: “The management backed me because they believed in the story.”

Despite the MoS investigation, the UK government dragged its feet over sourcing safer, but more expensive, heat-treated blood plasma and infected blood stock continued to be sold around the world.

Douglas said: “Looking back on it, it should have happened much faster and in a genuinely free press, probably things would have moved more quickly.”

Does Douglas believe the Infected Blood Inquiry would have happened without the actions of journalists? “No, and by the way, I think it can happen again and again. With the public inquiry there is a sense of relief that there is an ending. But it’s not an ending because it could happen again.”

Citing the example of the now withdrawn Pfizer Covid vaccine, she said: “Do we know really what the long-term effects were of that particular vaccine for people who could have suffered undue blood clotting? No, we still don’t know.

“But I’m sure the medical research exists, where’s the transparency on that?”

Douglas went on to become editor of the Sunday Express and hold senior executive positions at Conde Nast and Trinity Mirror (now called Reach).

Asked how she feels about the future of tabloid investigations like the one which launched her career she said: “I don’t think the revenue model really is there anymore. People expect to have content for nothing…

“The other thing is, do they even exist? If you look at Mail Online now it’s largely clickbait. It’s quite often stuff that, does it matter very much, I don’t know? There are very few investigative stories anywhere and they cost a lot of money.

“When I was on The Sunday Times Insight team we would get something like 17 page leads per annum, a lot of dead ends and two, if you were lucky, big, big front-page stories that would run.”

She added: “People think that social media is an answer and that we can all generate content, but nobody actually acts on any of that. You have to stand up at some point and make a big deal, which is why I really will always believe in the tabloid press.”

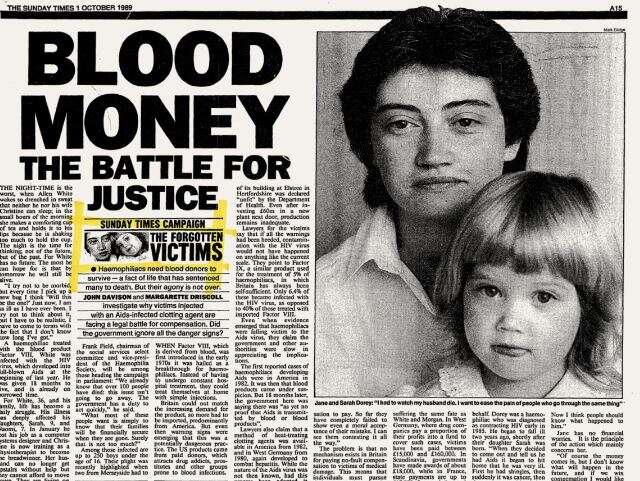

Caroline Wheeler’s 23 years reporting on the infected blood scandal

Sunday Times political editor Caroline Wheeler first began reporting on the infected blood scandal 23 years ago when she was working on the Sunday Mercury newspaper in Birmingham aged 21.

A man called Mick Mason called her up to say he had been infected with hepatitis C and HIV via a blood transfusion and had been warned that he may also have contracted the deadly brain disease CJD.

She said: “I had to go away and look through the archive to understand what he had been telling me and everything turned out to be true. It began an interest which I have taken to every paper I’ve been working with since.”

Last month Wheeler was sat next to Mason in the House of Commons gallery and both were close to tears as Prime Minister Rishi Sunak issued his apology to the victims of the scandal. He described the publication of the Infected Blood Inquiry report as a “day of shame for the British state”.

She is pictured below with another victim and one of her many sources for the story, Ade Goodyear.

Wheeler continued reporting on the issue whilst working as a lobby correspondent for a group of regional newspaper titles which are now in the National World stable. She joined the Sunday Express as political editor in 2014 and helped launch a new infected blood scandal campaign for the paper.

She said: “It started with the story of Treloar’s, the school where children were infected with hepatitis C and HIV through contaminated blood that they received as part of a series of medical experiments.

“It was the first time in a long time journalists had gone back after the original scandal in the mid-1980s and documented the sheer scale of the loss of life at this stage.

“In 2014 we could report that scores of those schoolchildren had died. In fact of 122 haemophiliacs that attended that school from 1975 onwards, only 30 of them are still alive today.”

Around the time of the 2015 UK general election, Wheeler worked closely with Labour MP Diana Johnson to campaign for political parties to put in a manifesto commitment to support a public inquiry into the blood scandal.

The Liberal Democrats were the first to agree and by the time Theresa May had called the 2017 general election all the opposition parties with parliamentary seats supported a public inquiry including (crucially) the DUP who would hold the balance of power in a subsequent hung parliament. It was around this time that Wheeler moved to The Sunday Times as deputy political editor (she was promoted to political editor in 2021).

She said: “About a week after the election result I bumped into Diana Johnson walking across Portcullis House and we started talking about what to do with the campaign next. I mentioned casually that it’s quite significant the DUP have now backed a public inquiry and does that mean we’ve got a majority of party leaders and a majority of MPs that might support a public inquiry?

“We came up with this plan to get a letter signed by the leaders of the parties that supported a public inquiry and it ended up making about 400 words on page four of The Sunday Times.”

The letter prompted speaker John Bercow to suggest Johnson apply for an emergency debate on the issue.

“And about two hours before the debate was due to take place, I got a message to call Downing Street which was unusual because normally they just, you know, call me on my mobile phone.

“But I called and I got put through to the prime minister’s press secretary who said ‘well done – two weeks into your new job at The Sunday Times, you’ve got your public inquiry. The Prime Minister is going to announce it in a couple of hours’ time’.”

‘The proudest moment of my career’

Wheeler added: “I think that was really the proudest moment of my political career. It was the moment where the hair stood up on the back of my neck and I couldn’t really believe it was happening because we just never had felt that we were ever getting that close.

“It felt like there had been quite a lot of howling into the wind and a lot of people that had kind of decided that this issue had been put either in the too difficult box or in the not going to happen box. And to finally get this public enquiry was unbelievable.”

The inquiry opened in 2018 and finally reported its findings last month listing a catalogue of failures including the government waiting until the end of 1985 to heat-treat blood products in order to eliminate HIV, long after the Mail on Sunday highlighted the risks.

Asked whether the Infected Blood Inquiry would have happened without the actions of journalists, Wheeler said: “I always think it’s a wonderful thing when you get a kind of real partnership between newspapers and politicians.

“The establishment and Westminster are to blame for so much of what went wrong. But I think it would be wrong to conflate that and not see that actually there there is still a role for really good campaigning in our parliamentary democracy. And in this particular instance there was this wonderful coalition between the campaigners, the politicians and the journalists that really pushed this up the hill.

“It does show that there is still a role for really good campaigning journalism.”

‘Good journalism can still make a difference’

Wheeler emphasised that she “stands on the shoulders of giants” in terms of the work done by journalists before her, highlighting the work done by Margarette Driscol who worked on the Forgetten Victims campaign for The Sunday Times along with reporter John Davison under editor Andrew Neil. It helped to secure improved compensation payouts for victims and their families.

Wheeler said: “I absolutely pay tribute to all of those people that have been involved because I think it’s been a massive team effort. It’s a moment where we can take some pride as journalists that good journalism still can make a difference.”

But why, as with the Post Office Scandal, has it taken so long after all this campaigning journalism began for the infected blood scandal victims to secure justice?

“In the 1980s and indeed the 1990s there was a real intransigence in government to want to do anything about this. The feeling amongst consecutive governments was that they didn’t want to pick up the tab for this particular disaster.

“We’ve got front page after front page after front page and I think what happened was the government just inched forward.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog