It can seem glib to compare the current era to the 1930s. There are parallels, with the rise of nationalism and the free press under attack, but we are a long way away from Nazi-style totalitarianism returning to the West.

Nonetheless today’s journalists can learn much from the way our predecessors dealt with the challenge of reporting on the rise of Hitler in Germany. Some showed courage in the face of oppression which should inspire us, but we can also learn from the folly shown by others.

One man who does appear to have learned the lessons of history is the current Lord Rothermere, the proprietor of the Daily Mail.

We now know that he not only ignored Prime Minister David Cameron’s pleas that he sack editor Paul Dacre over his anti-EU campaign, but that he did not even mention the matter to Dacre until after the EU referendum (even though Rothermere himself is said to be pro-European Union).

Rothermere (Jonathan Harmsworth, 49) will well know the dangers of proprietorial influence given his great-grandfather’s enthusiastic support for fascism and Hitler in the pages of the Daily Mail in the 1930s.

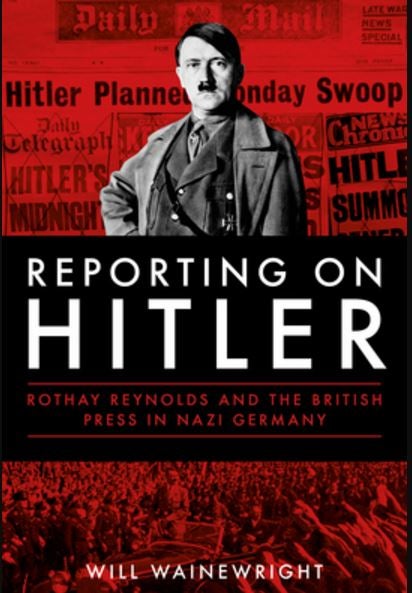

The extent of that support is revealed in a new book by Will Wainewright called Reporting on Hitler.

The first viscount Rothermere assumed control of the Mail following the death of his brother Lord Northcliffe in 1922.

Together with Daily Express proprietor Lord Beaverbrook, Rothermere campaigned for a British Empire free trade area – and high tariffs for elsewhere. He even formed his own United Empire Party to further this aim.

In 1931 Conservative Leader Stanley Baldwin said the Mail and Express were the “engines of propaganda for the constantly changing policies, desires, personal wishes, personal likes and personal dislikes of two men”.

He added famously: “What the proprietorship of these papers is aiming at is power, but power without responsibility, the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.”

Following the 1930 German federal election, in which the Nazis won 107 out of 577 seats, Rothermere wrote in the Mail that Hitler’s party “represent the birth of Germany as a nation”. This was at a time when Hitler had made clear his hatred of Jews and belief in racial supremacy in his book Mein Kampf.

The Mail was rewarded with exclusive access, publishing several interviews with Hitler throughout the 1930s.

In March 1933, Hitler’s party won 288 seats and 44 per cent of the vote.

Welcoming the result in an editorial the Daily Mail wrote that if Hitler used his majority “prudently and peacefully, no one here will shed any tears for the disappearance of German democracy”.

After the June 1934 “Night of the Long Knives” in which Hitler murdered more than 100 political opponents, the Daily Mail report began: “Herr Adolf Hitler, the German Chancellor, has saved his country”. In December that year Rothermere and his son Esmond were the guests of honour at a dinner party hosted by Hitler.

The Mail also welcomed Hitler’s remilitarisation of the Rhineland, in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles.

In the early 1930s, Rothermere was so close to Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists that Daily Mail staff began to mimic their dress – wearing black shirts to work, Wainewright reports.

The nadir of this period was a Daily Mail article headlined: “Hurrah for the blackshirts” which concluded with a direct call for young men to join Oswald’s party.

In fairness to Rothermere, his support for Mosley evaporated when he saw the violence and antisemitism associated with his group. And he at least foresaw the potential threat from Germany, and campaigned for rearmament, whilst papers on the left – such as the Guardian – were critical of Hitler but opposed rearming.

In the late 1930s Wainewright notes that much of the UK press was guilty of soft reporting about Hitler and Nazi Germany under pressure from Prime Minister Chamberlain who urged editors not to publish anything which might anger Hitler and undermine peace efforts. The Fuhrer was apparently extraordinarily thin-skinned when it came to criticism from Fleet Street.

Events in Germany were not uniformly condemned in the British press until the November 1938 anti-Jewish pogroms on the Night of Broken Glass, Wainewright writes.

Journalists who reported the truth from Germany in the 1930s risked arrested by the Gestapo and expulsion, but many did.

Among them was Phillip Stephens, writing in the Daily Express, who was arrested after reporting about the effect of the international trade boycott on Hamburg in 1934. He went on to write days later about “Jew baiting”, segregation and attacks on synagogues. He was arrested again and given 24 hours to leave the country.

Sefton Delmer told the true story of the Night of the Long Knives killings in a front-page story for the Daily Express published on 6 July 1934, and narrowly avoided expulsion from the country.

In the late 1930s Evening Standard cartoonist David Low outraged both the UK and German governments with his work lampooning the appeasers.

In 1937 The Times angered Hitler by reporting on the massacre by German bombers of 1,000 civilians when they attacked the Spanish town of Guernica in support of General Franco in the Spanish civil war. It led to a wave of anti-British sentiment in the state-controlled German media, Wainewright reports.

And in a leader column which would not be out of place in some US newspapers today, The Times said at the time: “What is the destiny of the world in which no responsible organ of the press can tell the simple truth without incurring charges of Machiavellian villainy?”

Looking at last year’s EU Referendum, some have talked about the corrupt hand of the press owners on that campaign. Our market-leading national newspapers – the Mail, Sun and Telegraph – were slavish in their support of a Leave vote.

But at the Daily Mail a least, which is probably the UK’s most influential newspaper, it was journalists (and one editor in particular) who were calling the shots.

Wainewright’s book quotes a journalist’s complaint to the post-war Royal Commission on the Press about “journalistic knowledge, experience and sense of responsibility to the public being overridden by the fiat of a press lord” in the 1930s.

Whether you agree or disagree with his stance on the EU and other matters, I suspect Dacre is driven by a sense of “responsibility to the public” and of what resonates with this readers. The current Lord Rothermere deserves credit for allowing him a free hand.

Reporting on Hitler, by Will Wainewright is published by Biteback, price £20.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog