Press Gazette joined a host of famous names from broadcast journalism to mark 50 years since the launch of LBC, the UK’s first licensed commercial radio broadcaster.

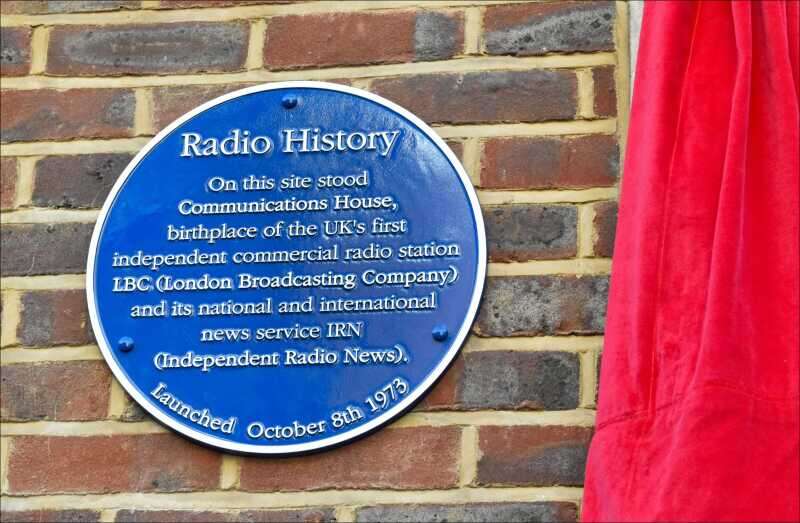

LBC alumni including BBC correspondent Clive Myrie, Today presenter Martha Kearney and former Conservative MP Gyles Brandreth were among those to attend the unveiling of a blue plaque on Friday at the site of its old offices near Fleet Street.

LBC and its news bulletin service Independent Radio News (IRN) launched on 8 October 1973 in the now-demolished Communications House in Gough Square, Holborn.

Day one: ‘Alfonse was playing with his rubber duck as he broadcast’

Dame Jenny Abramsky, the former head of BBC Radio who in 1973 was working as a producer for the corporation, recalled that on hearing the first broadcast of LBC: “The BBC’s first reaction was: ‘Oh, this isn’t going to be a problem.’”

Heather Branwell, the former LBC producer who was driving the desk on the first day, told attendees on Friday: “It was pretty awful. Nothing was finished. There was a man underneath the desk still wiring things up as we were going on air…

“I think all the ads had been recorded in another studio, so they weren’t compatible with our machine.”

Management, she said, were meanwhile having a very loud party and had to be asked by a producer to leave.

Gyles Brandreth told the crowd he was paid £5 for his work on the first day at LBC.

“There was anxiety as to whether people would listen to the commercials. So I was engaged, before every commercial, to set a riddle and then give the answer of the riddle after the commercial to entice people to listen.”

The first riddle issued on Monday 8 October 1973, was: “Take the letters M, O, N, D, A, Y and rearrange them into another word that expresses the essence of what LBC is going to be all about.” (The answer was dynamo.)

Brandreth added that, “as I was saying this, I could see out of the corner of my eye the corridor. Because on day one, there was no door to the main studio… there was somebody, paid even less than me, and even younger than me, to stand in the corridor going: ‘Shh!’

“I stayed and then did the night shift, where there was a wonderful character after midnight called Alfonse. Our only caller between midnight and 2am. We had to stick with Alfonse. His fantasies got worse and worse. He was in his bath. He volunteered to show us his rubber duck. And he said he was playing with his rubber duck as he broadcast.”

Douglas Cameron, who was then working at the Today programme when LBC launched but would join the station the following spring to present its AM programme, told the attendees: “We were listening to it, and what we heard was, quite frankly, dreadful.

“I know a station’s got to start staggeringly, but this one really did stagger. And, unfortunately, the publicity department, eager to get things going, issued a little memo saying: ‘You’ve never heard anything like it.’ And my God they were right, because it was awful.”

But he added: “The BBC in those days was just a little bit stodgy… a lot of the [LBC] presenters said, well, we’ve got to be one of the people, one of the public – we’ve got to not read the news to them, we’ve got to tell them the news.”

Cameron said the station’s coverage of the Falklands War in 1982 was what ultimately brought LBC’s approach to the news professional esteem.

Al Jazeera diplomatic editor James Bays, who was in town from New York for the unveiling (and his mother’s 80th birthday), said LBC had been “the maddest, most lovely place I ever worked”.

He had not travelled the furthest to be there on Friday: former LBC producer Cathy Jacobs had come to the unveiling from Australia.

They said that “quite a few Australians seemed to find their way to LBC”, because commercial radio was already established in Australia.

Grain-powered broadcasting

MC’ing the event, Today programme presenter Kearney said that if some attendees’ memories of LBC’s earliest days were blurry, “I was thinking it was because we really should be erecting plaques to The Cheshire Cheese, to The Tipperary, to The Wine Press, to the Dive Bar and the workers, where so many animated editorial discussions took place”.

BBC home editor Mark Easton said there had been “quite a lot of alcohol involved” in work at LBC.

He told the crowd: “I remember my first day I turned up – I was 22 years old or something – and I think it was [IRN deputy editor] Steve Gardiner who said: ‘No, you need to come around to the pub around the corner.’ I went round there – it was 11 o’clock in the morning and there was a man standing at the bar who I later discovered was Bill Deedes, the then-editor of The Daily Telegraph. And it was explained this was my first day in Fleet Street. And he said: ‘You’ll need a whiskey. A large one!”

“So that was my introduction to Gough Square. And the drinking never stopped.” Easton meant this literally: he explained that the presence of the printing presses, Smithfield meat market and other industries nearby meant at least one drinking establishment in the area was selling alcohol at almost every point in the day.

Opportunity, actuality and better ways to broadcast

McGarry, who had been intake editor at IRN, told Press Gazette that when LBC launched: “The BBC were so locked into doing what it did and had done since the thirties.”

He said the BBC’s system was “super expensive and bonkers”.

“I worked at the BBC when I came from Australia in ‘71, having worked for two years in commercial radio there,” McGarry said.

“I was astonished to see reporters coming back [from the field] with huge tape recorders and then giving it to a desk of ladies who had to then transcribe it – and then would give the paperwork back to the [reporter] who would then say what this person [the interviewee] had told him.

“They didn’t even play the actual voice – or as we called it in IRN days, ‘actuality’.”

Several former staffers described “actuality” as one of LBC’s most lasting contributions to broadcasting.

Easton said: “LBC/IRN just changed everything in terms of the way that talk radio and news radio was done. It was all about being there at the time of sending your reports.

“People like Jon Snow, who was an early reporter there – he actually broadcast from the Balcombe Street siege on a walkie talkie… he was able to broadcast live. No one else could do that.

“The BBC in those days had their very strict schedule so they couldn’t break out. So actually LBC/IRN were able just to say: ‘Story’s broken!’ I mean, nowadays it feels so obvious. But then it was absolutely groundbreaking…

“When this place first opened its doors, the only place you could get 24-hour news was here.”

Kearney and another prominent present-day BBC presenter, Clive Myrie, added that LBC had been an ideal place to begin a broadcasting career.

Kearney said it had been “quite emotional coming back to Gough Square”.

“This is where my career began as a newsroom secretary, as a phone operator on phone-in programmes, before becoming a trainee and then going on to be a reporter.

“And it was a brilliant place to learn because it wasn’t at all well-staffed, so we all had a go at doing pretty well everything. It was quite chaotic, quite anarchic. But it also gave birth to a new way of telling the news where we would go live to stories, where we would use the sound of the story we were on in a way that’s commonplace [now], but 40, 50 years ago was very unusual.”

Myrie told Press Gazette that “The way that LBC/IRN communicated the news is the way that everyone does it now. It’s relaxed, it’s informal and it’s a friend just telling you what’s going on during the day.

“That was not the case when I started in this business, and it certainly wasn’t the case at the BBC. The BBC has moved towards the model that these guys and women and brilliant people had put out there for years. And the rest of the world’s caught up. It’s as simple as that, and I think that’s amazing.”

Separately he told the crowd: “What I love about IRN was that they were willing to give young reporters like me big, significant stories.

“I went to Northern Ireland for the first time [for IRN] and Vince [McGarry, the IRN intake editor quoted above] came to me just before I left and he said: ‘Clive, be careful out there. They may think you’re a foreign soldier and shoot you in the head. Good luck.’”

LBC, originally the London Broadcasting Company, today stands for Leading Britain’s Conversation and has a weekly reach of more than 3m according to Rajar.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog