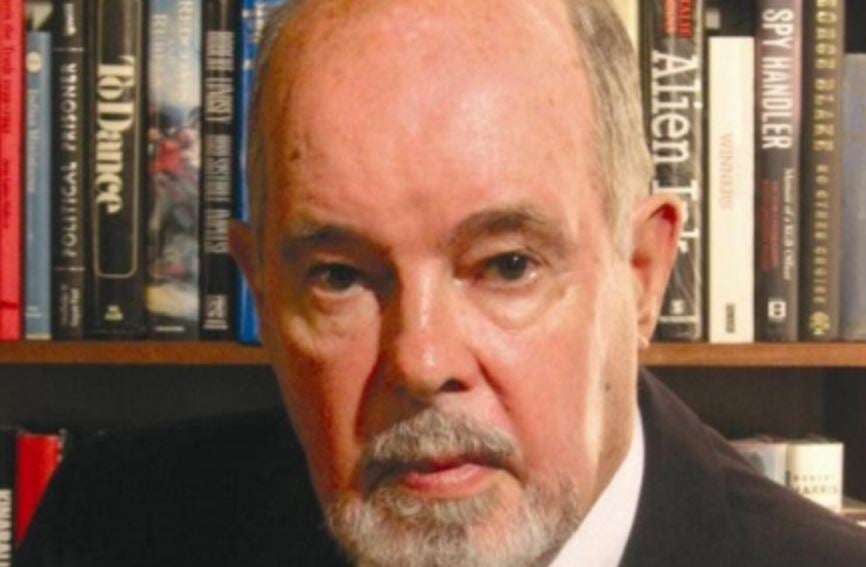

The Sunday Times journalist who led the paper’s investigation into the Thalidomide scandal, Phillip Knightley, has died aged 87.

The story was the defining project of Harold Evans’s celebrated reign as editor of the paper from 1967 to 1981.

In 1972, The Sunday Times sought to highlight the plight of the 370 known victims of the drug thalidomide, which caused major birth deformities in babies.

The UK distributor of the drug, Distillers, had offered the victims total compensation of £3.25m.

The Sunday Times campaign helped prompt Commons action and a shareholder revolt at Distillers.

A new compensation deal worth £32.5m was eventually agreed.

After fighting an injunction all the way to European Court, in 1976, the paper also revealed that the drug’s developers had not met the basic testing requirements of the time before distributing it.

The story was based on company documents acquired by The Sunday Times, possibly illegally, for £10,500, which undermined its legal defence. Knightley pulled the material together into a 12,000-word narrative which showed the link between the drug and the birth deformities

Former Sunday Times insight team editor Robin Morgan told Press Gazette: “Phillip Knightley was an inspiration to generations of journalists.

“It always amazed me that during the frantic Saturday afternoons

when the then 54-page Sunday Times was being to put to bed in Grays Inn Road, Phillip could hand in 1500 words of neatly typed and spaced scoop and then take a nap under his desk, impervious to the racket around him and waking just as the galleys came up from the print floor.

“He was always immaculately dressed with a sense of the theatrical – his Lenin goatee topped off with a fur ushanka – but his writing was a triumph of distilled simplicity.”

Another former Sunday Times Insight editor, Christo Hird, told Press Gazette: “The thing about Philip was that he wore his skill and talent so lightly. He was diligent, methodical, measured.

“It was this that lead to him cautioning against the publication of the fake Hitler diaries – never make a deal under pressure, he said, recalling earlier similar errors. He was unfailingly courteous and helpful to less experienced people such as me and completely devoid of the office politics so prevalent at the Sunday Times in those days.

The Times wrote today: “Above all he was patient. He spent seven months exposing the tax privileges that had been granted, secretly, to the Vestey family, importers of meat from Australia and Argentina, for which he won ‘Journalist of the Year’ at the British Press Awards in 1980.”

His negotiation to interview Kim Philby, the Russian spy, in Moscow took 20 years. He finally spoke to him two months before his death in 1988 generating a famous exclusive for The Sunday Times

Knightley was born in Sydney and began his career as a copy boy at the Sydney Daily Telegraph before joining the Melbourne Herald as a reporter where he met a young Rupert Murdoch.

After various jobs, which included selling vacuum cleaners and peanut vending machines, he arrived on Fleet Street in 1963 aged 34, getting his foot in the door at the Sunday Times with a story picked up at a dinner party about a scam involving imported corned beef.

He was asked to look into another story – for the Atticus column – by news editor Michael Cudlipp, about pupils at Eton writing to the Communist Part headquarters asking for posters of Marx and Lenin. After being referred to Eton’s PR man, he was told by Cudlipp to instead interview the PR man – as this was seen as a better story.

The PR demurred, only to agree to a full interview after being pressed by Atticus editor Nicholas Tomalin.

Tomalin told him: “You lost that Eton story because you gave up too soon….Lesson: In journalism no no is ever final.”

Knightley went on to gain further shifts at the paper and then a staff job.

Ian Jack, writing in The Guardian today, said of Knightley: “The writing was unmannered and straightforward – it lacked any notable style or ‘personality’ – but it could clarify the most complicated (and often legally fraught) stories without sacrificing factual accuracy or losing the reader’s interest.”

Jack said: “Knightley was modest about his many achievements. He was lucky, he would say, to work on an overstaffed and generously funded newspaper with editors who would give him the time to chase after a story, and not complain if in the end it did not stand up.”

In his 1997 autobiography, A Hack’s Progress, Knightley said: “I know now that the influence journalists can exercise is limited and that what we achieved is not always what we intended. It is the fight that counts…

“My advice for a new generation of journalists is to ignore the accountants, the proprietors and the conventional editors and get on with it. And your assignment is the same as mine has been – the world and the millions of fascinating people who inhabit it.”

Knightley’s other successful books included: The First Casualty (a history of war reporting).

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog