The “shocking” lack of diversity in the UK’s newsrooms is making young journalists of colour feel “disenfranchised”, “alienated” and “isolated”, Press Gazette has heard.

It also means they feel “uncomfortable” objecting to coverage they believe is racially insensitive or racist, most recently around issues like police brutality and Meghan Markle, for fears of putting their careers at risk.

Three female journalists aged 30 or under spoke to Press Gazette about their experiences after we were told of a “culture of fear and cliquiness” in some newsrooms .

A 2016 Reuters Institute report found that women are “still very much a minority” in senior editorial positions despite forming a majority among young journalists.

It also condemned a “chronic failure to achieve even reasonable levels of ethnic diversity”, giving the example that black Britons are under-represented by a factor of more than ten in UK newsrooms.

‘You don’t want to impact your career’

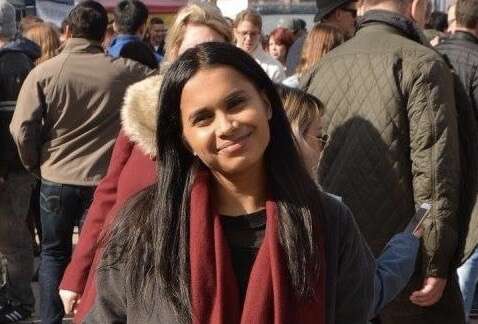

Khaleda Rahman (pictured, bottom right), a reporter at Newsweek in London, told Press Gazette she at times felt unable to speak up about issues in her previous newsrooms. She has also spent time working in New York, LA and Sydney.

The 30-year-old pointed to times she felt she had a “viewpoint based on my background but felt uncomfortable expressing it”. On other occasions she felt coverage was either “racially insensitive or just outright racist”.

“Sometimes you can say something depending on who the editor might be, other times you can’t, and obviously being in a junior position you don’t want to impact your future,” she said.

“As a freelance reporter, I worried about damaging relationships with editors because you that’s how you make your living.”

Rahman added that newsrooms cannot rely on one journalist of colour to speak up about problematic headlines or other mistakes.

“There’s so few of them they’re not always going to be around to spot the issue and they may not feel like it’s worth them fighting for one headline when more broadly things won’t change.”

Rahman said she was once advised by an editor to anglicise her name “for a better chance at securing an interview”.

She was also asked by a local newspaper editor during one of her first ever interviews “if residents in a predominantly white area would feel comfortable speaking to me”.

“Unsurprisingly, I didn’t get that job,” she said.

Khaleda Rahman. Picture: Louise Quick/louisequick.com

Rahman said she has also noticed nepotism as a particular issue in newsrooms, meaning “for many people of colour, those from working class backgrounds and those who don’t have contacts in the industry, getting your foot in the door in the first place is a massive hurdle to overcome.

“And that’s before entering a newsroom where you often feel you have to work twice as hard to get the same recognition as some colleagues.”

‘No change’

She said she has seen no improvements in her seven years in the industry because newsrooms hire from diverse groups but don’t provide sufficient opportunities to progress or offer inclusion training to staff in their newsrooms to understand their unconscious biases.

“The only way to have a bigger impact and more lasting change is to have diversity across the board in newsrooms in editor positions, in senior reporter positions, in the positions where you can make a change rather than just having a few trainee reporters who are from different backgrounds but end up leaving because they are not being promoted or not being valued.”

Helena Wadia (pictured, top right), a video journalist at the Evening Standard who previously worked in a number of broadcast newsrooms, agreed that while hiring diverse candidates is “one of the best things you can do”, inclusion must also be an essential part of the strategy.

She called for compulsory training on race-specific issues.

“For example, mixing names up and how to handle certain things sensitively,” she told Press Gazette.

“It’s frustrating sometimes – I’ve been in meetings where people have said quite racist, stereotypical jokes for example about Muslim people and you feel like it’s your duty to speak up but you’re also scared because you’re the one brown woman at the bottom of the rung and you don’t want to do anything that could jeopardise your career or that job because it was hard enough to get in anyway.”

‘I just want people to care’

Wadia added that it’s not enough to arrange inclusion training “and then wash your hands of the issue”.

“Nothing’s going to change really until diversity is top of the priority list,” she said. “I just want people to care and do the work.”

Helena Wadia

Wadia has often had the feeling of “looking out into a sea of white faces” in newsrooms.

“I’ve mainly worked in London and some of the newsrooms I’ve worked in, you look around and think how does this reflect the multiculturalism of London?

“I’m Indian and there’s often one other Indian woman who looks nothing like you but you get called her name and she gets called your name over and over again.

“Another main experience is that I’ve repeatedly pitched ideas that are dismissed because they’re not relatable but what those mostly white, mostly male editors and commissioners are saying is that ‘it’s not relatable to me’.

“But if there were more non-white, female, transgender, LGBT, working class people in senior positions of power then these issues would be discovered and ‘relevant’, talked about, you could really help people.

“If you see journalism as something that helps people delivering accurate up-to-date information to the masses then you’ve got to include all the masses.”

She added that when an issue that directly involves people of colour, like Black Lives Matter, emerges to the mainstream young reporters are then “called upon to put your heart and soul and every experience of racism you’ve ever had into your journalism and you question why wasn’t I being listened to before?”

Wadia also criticised the way issues relating to race and racism are frequently “set up as a matter of debate”, particularly on radio and TV.

“Those debates would happen far less frequently if there were people of colour in more senior editorial roles,” she said.

Asked how she feels to see all this going on in the industry she works in, Wadia said: “It makes me feel a bit disenfranchised maybe. It feels like a struggle basically.

“But on the other hand it also spurs me on in a way because I think it’s going to be so much better when my generation and people like me get further up. I see that as a real opportunity for change and that makes me very excited. But day-to-day it can be quite isolating.”

Wadia did praise London Live, which she said got excellent stories from journalists who were young and old, white and non-white, male and female, and gay and straight.

“I think it is an example that your newsroom will do better and flourish,” she said.

She also singled out 5 News for its strong gender diversity and the way it decides whether stories need a diverse voice to tell them properly, and if the answer is yes, don’t run them without one.

However Faima Bakar (pictured, left), a 26-year-old lifestyle reporter at a major UK news website who has done casual shift work at a number of national titles, told Press Gazette “every single newsroom” she has worked in has a “glaring” diversity problem with almost all white staff and most senior positions filled by men.

This can feel “alienating,” she told Press Gazette.

“As a minority, you feel like you stick out just by existing. You become the representative of the group you belong to. People ask you weird questions, things they can easily Google.”

Bakar, who was recently named one of 30 young journalists to watch, said she has been mistaken for the only other Asian woman in the room “despite not looking anything like her”.

She added that she once “heard another ethnic minority writer be referred to as ‘foreign’ even though she is as British as you can get”.

Newsrooms make ‘disheartening’ mistakes

Referring to recent high-profile incidents such as the Guardian using a photo of the rapper Kano instead of grime artist Wiley and a white BBC journalist using the N-word, Bakar said these were “lazy, and boring mistakes now”.

“It’s careless and egregious. It’s disheartening because I really believe that no other minority can feel free until black people are freed from the horrific anti-blackness they face.”

Bakar acknowledged that every industry must deal with a lack of diversity but said the media “especially has a duty to be reflective because it frames the narrative for what people think and believe”.

“That’s a massive power,” she said. “When newsrooms are overwhelmingly white, it means they’re not in tune with marginalised voices and things these groups care about. It becomes easy to stick to lazy stereotypes.”

Bakar urged newsrooms to make an “active effort” to hire more black, Asian and minority ethnic people but said they must also “ensure those people can actually progress” and that they are nurtured, happy and not overlooked for promotions.

“I think with the Black Lives Matter protests, a lot of publications promised more diversity and reached out to lots of black and minority voices – but where are those voices now? How many of them were actually employed or moved up in their role?”

Action and recommendations

Social enterprise Creative Access, which helped Rahman and Wadia secure paid internships earlier in their careers, published a list of long-term recommendations for creative industries as part of its More Than Words campaign encouraging action on diversity.

The organisation places around 50 to 60 young BAME journalists each year with the likes of the FT, Reach, the Guardian, BBC, Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Telegraph, Times and Hearst.

Its recommendations include re-assessing company brand values to ensure diversity is at their heart and not just an “add-on”, carrying out a full data evaluation to identify any patterns in relation to who gets recruited and retained and any micro inequities in teams, setting diversity targets to be reviewed regularly, and asking every employee anonymously how they feel the company is doing.

They also back up calls from Rahman, Wadia and Bakar for both positive recruitment progression of under-represented staff, sufficient opportunitiy for them to progress, and training that helps everyone “understand the benefits of a diverse workforce, identify and overcome their unconscious biases and become allies”.

The National Council for the Training of Journalists has been running the Journalism Diversity Fund for 15 years, helping 380 students from disadvantaged and unrepresented backgrounds through their training.

Journalism Diversity Fund recipients at NCTJ’s equality, diversity and inclusion conference in 2019. PIcture: NCTJ

It has now convened a forum to advise media employers what action they should take to improve equality, diversity and inclusion in their newsrooms.

It has also appointed a diversity and inclusion co-ordinator for the first time.

NCTJ chief executive Joanne Butcher said: “We recognise that tackling inequalities and making journalism better reflect our audiences needs the combined efforts of the industry, businesses, employers and journalists.

“We also appreciate that although this is a tough time for our industry, we need to be bold and to tackle the issues on a much bigger scale to achieve our ambition.

“The NCTJ will do as much as it possibly can to help media businesses attract and retain diverse talent and a broader range of voices in journalism.”

The image used of Faima Baker was updated on her request on 9 June 2025.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog