Satire and literary magazine The Fence is something like a cross between Private Eye and the London Review of Books.

Its readership is small but influential, with Michael Gove MP among its newsletter audience.

Press Gazette visited the publication – which bills itself as “the UK’s only magazine” – to learn why its staff are betting on a print-first, advert-free strategy.

What is The Fence?

Wedged between former nudie theatre The Windmill and yuppy bar Archer Street is the Soho office of The Fence. Across the road is the former Red Lion pub where Marx and Engels were given perhaps the most influential freelance commission in history, The Communist Manifesto.

The Fence is one of several creative start-ups given space on the cheap by Soho Estates, the property company that owns buildings throughout the fashionable area. The magazine’s staff occupy a small second floor room overlooking the street.

“We somehow forgot how fucking hot it gets in here,” Séamas O’Reilly, the features editor, told Press Gazette. His recent memoir, “Did Ye Hear Mammy Died?,” has pride of place on the office windowsill.

The publication launched in 2019 and moved into its current somewhat tumbledown premises in August 2021. It now numbers four staff, only one of whom, editor Charles Baker, is full-time.

Joining Baker and O’Reilly are deputy editor Kieran Morris and editor-at-large Fergus Butler-Gallie, who in his day job is a priest in the Church of England.

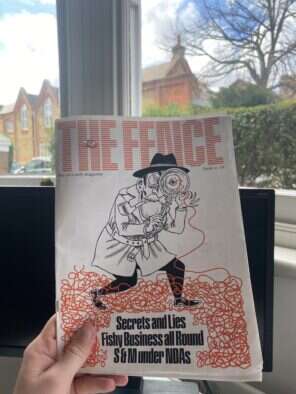

The magazine they together put out is a striking, picture- and advertisement-free production in black, white and orange, designed by art director Mathias Clottu.

Picture: Press Gazette

Like Private Eye – some of whose staff read The Fence – the magazine progresses through an esoteric mix of current affairs, gossip and comedic items, with an addition of essays and features.

Typical items might include an investigation into a spy at the height of British intelligence who was blackmailed for his S&M habit, a survey of the state of lesbian cinema or a true story about a powerful screaming cat .

“I think we’ve been able to sort of create a Fence brand of humour, which is broad-ranging and not especially cruel, but still very funny,” Baker told Press Gazette.

‘Silly and absolutely small’

Asked how the magazine had developed, O’Reilly said the publication has found a balance weighing “heavier, longer, 5,000 to 6,000 word pieces that do important reportage with slightly sillier stuff that we didn’t really see in other magazines…

“That niche has been really good for us to explore, but it’s also shown in the pitches that we get that are often from people who don’t get to write about silly things or smaller things.”

The magazine’s clarion call, according to Butler-Gallie, is “Pitch us the thing that you can’t pitch anywhere else.”

“I mean, that does get us some awful pitches,” said O’Reilly.

Issue 11 of The Fence. Picture: Press Gazette

Those that are not awful get published. O’Reilly cited as an example one item, “Why are you asking this?”, in which notable people are asked off-piste questions. The 11th issue of The Fence asked four Nobel laureates questions including “Who is the most beautiful person you’ve ever stood beside?” and “Can you do long division?” (Two said they couldn’t.)

Notably, The Fence is a young publication written by young people which nonetheless focuses primarily on print and only publishes that print product quarterly.

Baker said the set-up allowed their journalism to have “greater value”.

“Like two years ago, we did something where we commissioned somebody who works as an intelligence officer with the SAS to write about the SAS death squads… it was featured today in The Guardian’s newsletter.”

O’Reilly distinguished the less topical writing they were free to pursue at The Fence from the grind that faces many contemporary journalists.

“‘Okay, today you are an expert in, uh, Goblin Mode? I don’t know what that is because I’m a 55 year-old editor, but you have to be an expert in it in 14 minutes.’

“You put it up and you’re the nineteenth place to do a really bad 400-word thing on a concept which, four days later, no one will have a clue what you’re talking about.

“So a lot of our stuff is absolutely silly and absolutely small. But it has a sort of permanence. Firstly, because we write in print first and digital comes after. But also because, you know, it’s small because it’s meant to be small.”

The Fence business model

The self-conscious pursuit of print as a priority echoes the strategy Private Eye editor Ian Hislop outlined to Press Gazette last year.

“Everybody spent so much time on screen in lockdown, the last thing they want is something else on screen,” he said. “So a hard copy publication that you can sit in a chair – not on your screen – and read suddenly turns into a sellable item.”

[Read more: Ian Hislop interview – How Private Eye survived Covid-19 and why the BBC is under threat from ‘vindictive’ government]

Asked what he felt was driving growth at The Fence, Baker said: “The newsletter was a big thing that drove up subscriptions because it’s a way to engage with people… For some reason people reach into their pocket [when] they see an email in a way they don’t necessarily when they see a tweet.

“We’ve found that investigations and fiction are probably – we see the lowest return on investment with them. But they’re still an integral part of what we do.”

Butler-Gallie said it was “not dissimilar to other mags. People would open the Eye and look for the often quite lame jokes” before doubling back to the more serious stuff.

“And it’s that thing where, if I saw that in a magazine, I would put the kettle on and think ‘I’m gonna read that.’”

“All these things which are supposed to be handicaps have actually turned out to be strengths,” said O’Reilly.

“Maybe we should have died a death… but so far so good. I mean, we made a board game.”

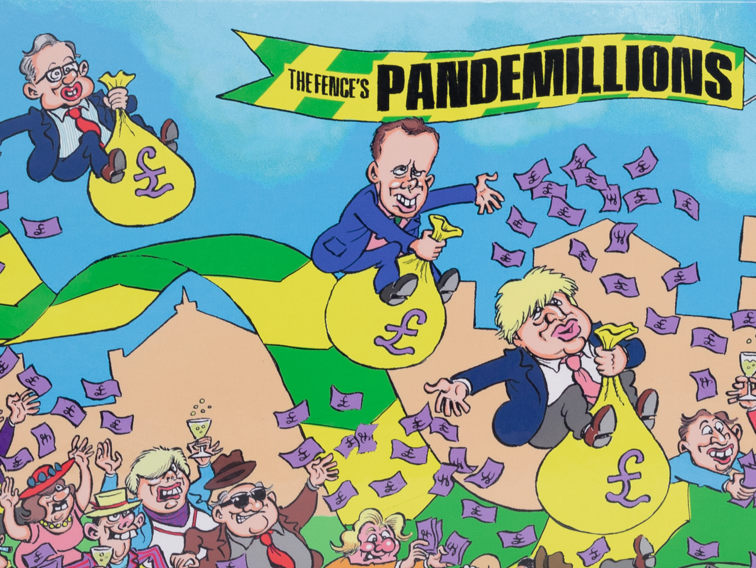

‘Pandemillions’

When Baker invited Press Gazette to The Fence office he said the staff would “show you the game and have a chat”.

Contrary to the assumption of Press Gazette’s reporter, “the game” was not an eccentric reference to the inner workings of The Fence but instead a literal reference to a board game.

Picture: The Fence

The game started “Basically as a visual aid” two years ago, O’Reilly said.

Pandemillions is set during the first lockdown. Participants play as members of the government “given unique access to the public purse to see their aims are met,” according to a blurb.

Gameplay inverts Monopoly: you win by spending as much public money as possible awarding contracts to your associates. As players advance round the board they draw “loot” and “chance” cards – many inspired by real events – which either help them unload cash into private coffers or pile them up with further burdensome public funding.

The aim of the game, O’Reilly said, “is you should just replay it and get angry.”

“All these things have been normalised, have been printed. Most of them you’ll even remember – you’ll be like – ‘Oh yeah I remember that!’ And then you’ll realise that nothing happened. No one has really seen much censure for it.”

The group found that when they mentioned the game to people, “the number one thing they said was, ‘Can I have one?’”, O’Reilly said. So The Fence manufactured 50 for sale: some 15 copies have been reserved and five will be given out for free.

Selling the game will not help grow The Fence’s business, despite the £50 price tag. Baker said they would feel “relatively uneasy” about profiting off a game which was, ultimately, sending up people who profited off Covid.

“The whole point is there are so many things here that are egregious and or specific to trying to be a profiteer,” said O’Reilly. “So let’s not be one of those.”

So where does the money come from?

The business in general is supposed to be for-profit, however. Beyond the decidedly unprofitable board game, Baker said, “we’re going to keep on driving subscription numbers up, but thankfully with the artwork, with the book, there’s lots of other revenue streams available to us as it grows.”

The book, “Sh*t literary siblings”, is an illustrated list of less-impressive siblings to famous fictional siblings – for example Paddington’s imagined brother, Euston Bear. It is due for release on 29 September – in time for Christmas, when The Fence makes 35% of its annual sales.

For now though, the business is not breaking even. But until it does it benefits from the most valuable boon a publication can hope for: a hands-off, idealistically-aligned benefactor.

Will Pelham, the 30 year-old second son of the Earl of Yarborough, “funds the magazine but he’s not involved editorially,” said Baker.

“He’s funded it since it started and I think it’s very – without being forelock-tugging, it’s very good that he gives the ultimate degree of independence, and doesn’t really get involved.”

He added that Pelham “gets immense satisfaction from seeing it grow as a business. And I think it’s a fun project for him to be involved with.”

Morris said it was “a mark of trust”.

“He sees that there’s an audience there. The audience has grown and grown and grown as we’ve developed, the style of the magazine has developed, and – yeah, I mean with every issue it grows prouder to be more involved in.”

For now, Pelham holds a narrow majority of the business’ shares, but Baker said ultimately the magazine would like further investment from other individuals.

Readers of esteem

So who are the audience to which Morris alluded?

We’ve got a very nice range of ages,” Baker said. “Our youngest subscriber is 17 and our oldest subscriber is 94.”

The gender split is approximately 55:45 men to women, with “a lot of subscribers in London”, though Baker stresses they have readers around the country and across political lines.

“We also have a disproportionate amount of American subscribers,” he added – approximately 7%, despite that “there isn’t much American stuff in there and it costs more to get to America”.

While most readers – at home and abroad – prefer to get their magazine delivered, Baker says The Fence is even stocked in a single newsagent in downtown Manhattan.

“I think they like how alien it seems to them,” said O’Reilly. “Which is a huge compliment because that’s what people loved about things like Spy, or before, things like Playboy.”

Asked who they were particularly thrilled to have as readers, the first person the group named was Spy co-founder and former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter.

After him, Baker named “The Viz magazine staff; Ben Schott; Chris Addison.” He looked around at his coworkers. “Is he a secret subscriber?

“No, he’s a big booster!” said Morris.

Staff at Private Eye and Popbitch were also name-checked.

O’Reilly added that besides full subscribers: “The newsletter goes to a lot of people.”

“Michael Gove reads it every time,” Baker said, “opens it every time, and never buys a subscription.”

Asked if they had a message for the MP, the group said, in unison: “Subscribe!”

Press Gazette is hosting the Future of Media Technology Conference. For more information, visit NSMG.live

This article was edited on 4/8/2022.

Picture: The Fence

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog