I met a man in my first weeks as a journalist whom I’ve never forgotten.

William Rutherford was a senior surgeon at Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital. It was 1981, at the height of the hunger strikes when ten republican prisoners died and the area around the hospital was in furious turmoil.

I’d grown up amid the Troubles but now I was meeting people deep inside the conflict. Within days, I went from seeing the body of a hunger striker who’d starved himself to death to meeting Rutherford, a man dedicated to preserving life.

What has stayed with me, more than the gun battles and the riots, the funerals and the fears of those years, was the humanity and humility of this man. He had simultaneously treated an IRA gunman and the British soldier the gunman had tried to kill. He’d seen every form of horrific injury a bomb and a bullet can do to a body.

But what moved him to the point of tears was recalling the children he’d lost in the operating theatre. That, he said, was the toughest part of his work. Losing a child to violence, then telling a mother or father the devastating news, turned those dark days much darker for Rutherford.

And there were so many dark days, when I thought the thin layer that separated Northern Ireland from even more brutal conflicts like Bosnia would be ripped away.

The massacre at Darkley, when gunmen crossed an unspoken moral red line by attacking a church service. The week when three IRA members were shot dead in Gibraltar, their joint funeral later ambushed by a loyalist gunman whose attack was caught on camera; just as cameras caught the full horror of the funeral days later of one of the victims when two soldiers were attacked and murdered.

After these, and a handful of other killings, we all felt anything could happen. The murders of the corporals seemed no different to me than the disgusting “necklace killings” of South Africa, when victims were burned alive by mobs setting fire to tyres around their necks.

Adrenaline rush of journalism

But amid all this, the dirty little secret of journalism was that it was exciting to suddenly find yourself covering mayhem and murder.

The sound of a nearby explosion had everyone in the BBC’s Belfast newsroom, and Radio Foyle where I also worked, reaching for a phone to the police or a coat to rush out the door, on the way perhaps bumping into Martin Bell, Kate Adie or Peter Taylor, giants of journalism for a cub reporter like me.

Nothing took away the horror of a murder scene, but for years it was an adrenaline rush to get there fast and file a report just minutes or hours later.

It was only after about a year in the job that it hit me. It was December 1982, and I’d been covering the massacre at the Droppin Well pub in Ballykelly where INLA bombers killed 17 people, 11 of them soldiers.

On the last of five days and nights on the story, I went back to my hotel room, sat on the bed and suddenly began crying uncontrollably. Everything I’d held in came pouring out.

It was the first time I realised that covering conflict can come with a price; a small one, often barely detectable, but one that eventually emerges, in anger, tears, alcohol or worse.

Eye for details

Often it was the small but heartbreaking details of atrocities that stuck in my mind.

The milkman shot dead on his float in South Belfast, his blood mixing with the milk from smashed bottles on the ground. The hideously dehumanised hooded bodies, bound and dumped on border roads after accusations of treachery and days of torture.

The gloriously sunny Saturday afternoon in Newry in July 1986: I can still see two of the three dead policemen, who’d been relaxing just a couple of hours beforehand with ice creams, slumped in their blue Ford Cortina, where they’d been shot by gunmen, at least one of whom wore a butcher’s apron.

We all learned to develop an eye for the detail that might add life to the story of each death, before the ritual condemnations and tired clichés of the politicians, and the chilling justifications of murder by the gunmen and bombers.

And I remember one other small detail of my first years as a reporter. Before the internet gave us Google and Wikipedia, journalists at the BBC in Belfast would hurry to the newspaper cuttings room, run by June Gamble, where the reports of every killing were compiled and filed.

There I often shuddered at the sight of the empty files on the table, numbered but not yet named, for those still alive who would be the next victims of our dirty little war.

Bill Neely is chief global correspondent for NBC News. He previously worked for BBC Northern Ireland, Sky News and ITN.

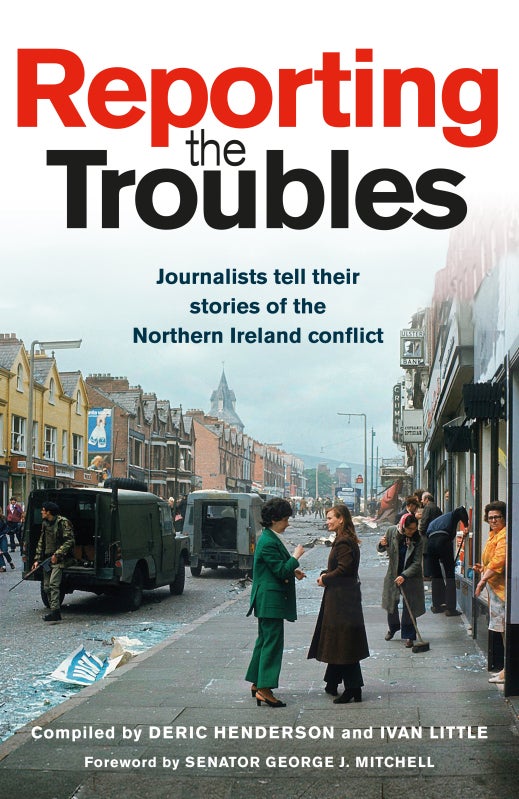

Extract from Reporting the Troubles: Journalists Tell Their Stories of the Northern Ireland Conflict, compiled by Deric Henderson and Ivan Little, published by Blackstaff Press, £14.99, 9781780731797.

Reporting The Troubles, published by Blackstaff Press.

Picture: MSNBC/Youtube screenshot

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog