The extradition of Julian Assange to the United States for his role in the Wikileaks release of classified US documents was approved by Home Secretary Priti Patel this month.

Under the 2003 Extradition Act, the Secretary of State must sign an extradition order once any legal grounds potentially prohibiting it are removed. This came in March, when the Supreme Court denied Assange’s right to appeal an earlier High Court ruling that greenlit his extradition.

Patel’s decision dashes one of the final hopes Assange and his supporters had of preventing his extradition. Although required by law to do so, Patel could have refused to sign the order without facing legal consequences, preventing the extradition which cannot go ahead without her permission.

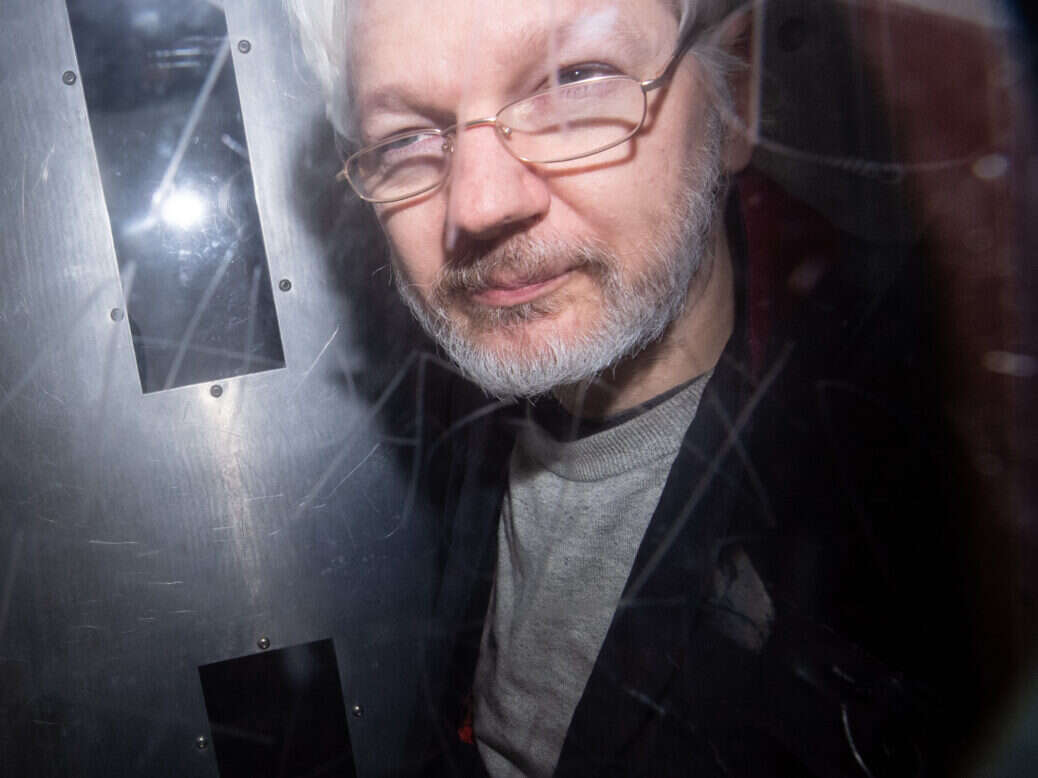

On the day of the announcement, Assange was taken from his cell in Belmarsh Prison and strip searched and moved to a bare cell, where he remained for the rest of the weekend, his wife Stella told PA. Here, he received no visitors whilst he processed the news that Mrs Assange described as “essentially a death sentence”.

Assange’s supporters and numerous human rights groups have critiqued Patel and the UK Government for failing to block the extradition, with Reporters without Borders calling this “another failure by the UK to protect journalism and press freedom”.

Assange now has until the end of June to appeal Patel’s decision, his final chance to avoid a 175-year sentence in the US following a decade-long battle involving UK, US and Swedish authorities.

Update: Assange lodged an appeal against the decision to extradite him to the US on Friday 1 July.

Is the future of press freedom at stake?

Assange, his team and his supporters have described the extradition as an attack on freedom of speech and a threat to journalists globally.

Following the approval, Mrs Assange described it as “a dark day for press freedom and for British democracy”. She added: “Julian did nothing wrong. He has committed no crime and is not a criminal. He is a journalist and a publisher, and he is being punished for doing his job.”

It has been a matter of debate for years as to whether Assange should be classed as a journalist; as political journalist Peter Oborne previously noted in Press Gazette, publications by Wikileaks included swathes of unedited documents that the US claims put sources’ lives at risk.

The Washington Post argued in 2019 following Assange’s initial arrest that he was “not a free press hero”, citing his tactics of “dump[ing] material into the public domain without any effort independently to verify its factuality or give named individuals an opportunity to comment” as not something a “real journalist” would do.

Nonetheless, many in the press feel as though Assange, journalist or not, acted in the interest of free speech and in line with common journalistic practice. Telegraph leader writer Philip Johnson argued soon after Patel’s decision that the extradition should “alarm anyone who wants to live in a free country”.

Andrew Neil also argued in the Mail following the announcement that the decision has stakes for the “future of a free press” and “its ability to undertake investigative journalism that embarrasses or shames the powers that be”. He added that the extradition would “chill investigative journalism…across the globe” and “embolden and empower those who want to suppress its ability to reveal unpalatable facts”.

In addition, the charges against Assange in the US are being brought using the 1917 Espionage Act, essentially branding him a spy. Tim Dawson, national executive member of the UK’s National Union of Journalists, told a rally in 2020: “The legal devices being deployed to try and take him to the US are unprecedented and terrifying for anyone whose journalism touches on state security, defence or espionage. If Assange is sent from here to start a prison sentence that could be as long as 175 years, then no journalist is safe.”

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange on the balcony of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London on 19 May, 2017. Picture: Reuters/Peter Nicholls

Who is Julian Assange?

Assange, an Australian national, is best known for founding whistleblowing platform Wikileaks in 2006. The organisation describes itself as a “a multi-national media organisation and associated library”, having released over ten million documents over its first ten years of operation, and has won numerous journalistic accolades, including from The Economist, Time and Amnesty International.

Nonetheless, its methods of bulk publication without editing are controversial, leading it to be accused of compromising the safety and privacy of sources and operatives in both civilian and combat environments.

Assange played a central role in the organisation, acting as its director and playing a key role in obtaining and distributing confidential material. Leaks have included emails from the Clinton campaign and Democratic National Committee during the 2016 US presidential election, nearly 300,000 emails from Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, as well as more than 750,000 documents, videos and files detailing US actions and alleged war crimes during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. One leaked video showed US Army helicopter operatives laughing while firing on and killing civilians and two Reuters journalists during the Iraq War.

What is Julian Assange accused of?

The US Government’s charges against Assange centre on the leak in 2010 alleging war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is wanted over an alleged conspiracy to obtain and disclose national defence information.

In 2018, the US alleged Assange both encouraged and assisted former US Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning to access and release privileged information. Manning spent seven years in prison following the event, and was jailed again in 2019 for refusing to testify in cases against Assange and Wikileaks, where she was largely held in solitary confinement for over a year.

A further 17 charges were brought in 2019 following Assange’s arrest in the UK, each under the 1917 Espionage Act, totalling a possible 175 years in prison should his extradition go ahead.

Julian Assange and the law: a timeline

In 2010, Assange was in London when a Swedish interpol arrest warrant was issued over allegations by two women of rape and sexual assault, both of which he has repeatedly denied.

Assange had previously hoped to move to Sweden and create a base for Wikileaks there due to its law’s protecting whistleblowers, according to the BBC, but his application for residency was denied.

After a long court battle, in 2012 the UK Supreme Court ruled Assange should be extradited to Sweden from the UK in order to face questioning.

Fearing extradition to Sweden would quickly lead to him being forced to the US over the Iraq and Afghanistan Wikileaks publications, Assange requested and was granted asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London on the grounds of protection of his human rights.

Assange remained living in the embassy for seven years. During this time, Swedish prosecutors dropped their investigation and rescinded their arrest warrant, yet British charges against Assange for violation of terms of his bail remained. A 2021 report by Yahoo News also revealed that Mike Pompeo and other CIA officials discussed ways to assassinate or kidnap Assange whilst he resided in the embassy following direction from then-president Donald Trump.

In April 2019, Assange’s asylum status was revoked by the Ecuadorian Government and Metropolitan police officers entered the embassy, arresting and carrying him out. He was sentenced to 50 weeks in prison for breaching his bail conditions.

Only following his arrest by British police was the original US charge against Assange from 2018, which was previously sealed but accidentally leaked by prosecutors, made public. The US also brought 17 further charges against Assange, requesting his extradition so he could be tried in America.

Protesters across from the Old Bailey, London, where a hearing in Wikileaks founder Julian Assange’s battle against extradition to the US began in September 2020. Picture: PA Wire/Jonathan Brady

This marked the beginning of a two-year legal battle in the British courts between Assange and the US Government.

A district court judge initially blocked the extradition request in January 2021, due to concerns that Assange would be at high risk of suicide if he was detained in a high-security US prison, citing medical evidence and Manning’s own in-prison suicide attempts.

Rejected were arguments in Assange’s defence in relation to his freedom of speech and political motivations on the part of the US, which press freedom campaigners had hoped could entrench protections for journalists into law.

In December, the US Government successfully appealed the decision to refuse Assange’s extradition at the High Court following assurances from lawyers that he would not be placed in a high-security prison.

Assange’s lawyers, however, have called these promises meaningless, describing them as “caveated, vague, or simply ineffective. None offer any concession or assurance against the application of existing US practice”.

The Supreme Court then denied Assange’s right to appeal the High Court ruling in March, stating that his bid to challenge the decision did not raise “an arguable point of law”.

This removed the final legal barrier preventing the approval of Assange’s extradition, allowing Patel to sign the order. His team has vowed to continue fighting and he has until the end of June to present his final chance to prevent extradition.

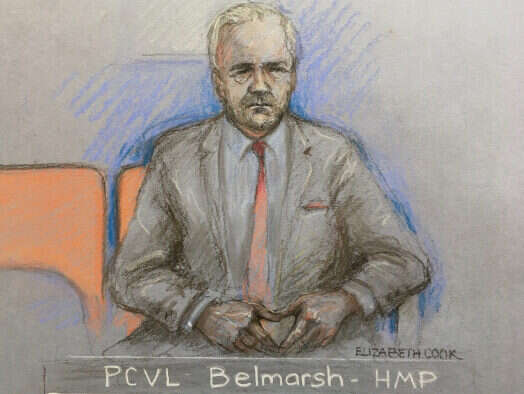

Court artist sketch by Elizabeth Cook of Julian Assange appearing via video link at Westminster Magistrates’ Court in London, after the Wikileaks founder was formally issued with an order to for extradition to the US to face espionage charges on Wednesday April 20, 2022. Picture: PA Wire/Elizabeth Cook

Picture: PA Wire

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog