Greg Miskiw, the former News of the World news editor nicknamed “the prince of darkness” for his part in the phone-hacking scandal, has died aged 71.

Miskiw served 37 days in Belmarsh Prison in 2014 after he pleaded guilty to conspiring to illegally access voicemails between October 2000 and August 2006. He was eligible for early release from his six-month sentence having already served 106 days of home detention with an electronic tag.

His daughter Sophie said the scandal “would sadly overshadow the great work he had done and what a remarkable journalist he was”.

Scroll down or click here to read a full tribute from Sophie Miskiw to her father Greg

She remembers a man who was under “crushing” pressure to produce exclusives and was “only ever seeking the truth” – but that he never downplayed what he had done wrong.

Sophie also described him as “fiercely loyal”, “defiant”, and a “restless soul”.

Before joining the NotW in 1987 Miskiw worked his way up the Mirror Group. Sophie recalls that he remembers his days as a reporter “most fondly”.

Miskiw spent 18 years at the NotW until 2005, running the newsdesk first in London and then briefly in Manchester after his actions on arranging payments for stories were deemed “cavalier and irresponsible” in a staff member’s employment tribunal. He also spent time as head of the news investigations unit which was closed in 2001.

He has said of his time at the paper: “You were in a bubble at the News of the World where the objective was very simple: just get the story. Just get it… no matter what… no matter how.”

But he was also “100%” certain other media groups had hacked phones, telling Channel 4 News in 2015: “If I’m a prince of darkness then I’m one of several princes. I’m more of a duke.”

After leaving the NotW in 2005 when he decided to turn down a job move back to London, he briefly headed up Liverpool-based Mercury Press Agency as editor and later went to Florida to work freelance and at tabloid The Globe.

It was not until 2011 that he became the 12th person to be arrested in Scotland Yard’s investigation into press phone-hacking.

At his sentencing almost three years later, the Old Bailey heard Miskiw had ordered 1,500 hacks from private investigator Glenn Mulcaire between 1999 and 2006, some even after he had left the paper.

The court heard that these hacking requests included murdered Surrey schoolgirl Milly Dowler – but in 2015 Miskiw told Channel 4 News he was “devastated” when he first found out from the Guardian that his colleagues had hacked Dowler’s phone.

Asked what he would say to the schoolgirl’s father, he said: “What could I say, other than: ‘I’m terribly sorry. It happened. It was more than misjudgment – it was an appalling thing to do.'”

‘My dad, Greg Miskiw’ by Sophie Miskiw

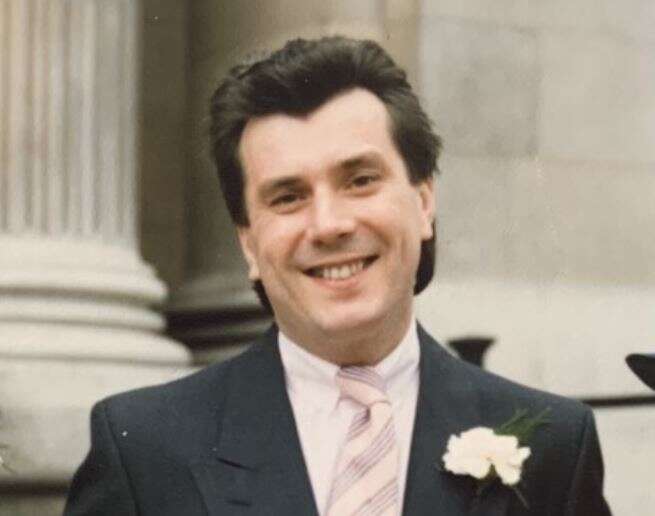

Greg Miskiw, aged 38, at his wedding to his ex-wife Sara at Marylebone Registry Office in 1987

My dad died in the early hours of Saturday 25 September. He went in his sleep – perhaps the first and last time he did anything quietly in his life.

He’d be annoyed about it. Dad always said he wanted to go out with a bang, not a whimper. But when you’re riddled with metastatic lung cancer, have ischaemic heart disease, diabetes and pulmonary hypertension, even getting yourself dressed is a struggle. So, I’m glad that dying, at least, was not.

In April this year, he had been rushed to hospital with a pulmonary embolism. In early August he was diagnosed with lung cancer. Seven weeks later he was dead.

Dad’s last years were a far cry from his glory days on Fleet Street. He never fully recovered from the time he spent in Belmarsh for phone hacking. He remained stoic, but the emotional and financial repercussions took a pervasive toll.

His health, which was already in bad nick, sharply declined. Perhaps worse – in his opinion, at least – his career and reputation were in tatters. The scandal would sadly overshadow the great work he had done and what a remarkable journalist he was.

He was still a teenager when he embarked on a career in journalism. It was an unusual route for someone of his background. Born in Leeds to Ukrainian immigrant parents, he barely spoke English until he was seven. Yet few people are so uniquely suited to their profession. Insatiably curious, with an almost preternatural determination, he had a knack for words and a sixth sense for sniffing out a decent story.

It was his days as a reporter that he would recall most fondly. He loved meeting people and rifling through their weird and wonderful stories. He collected them, and in his final months, found joy in recounting all the characters he had met.

Despite his fall from grace, Dad remained defiant and continued to tell his side of the story to Byline News, intent on revealing the true nature of the beast. He never downplayed his role in phone hacking, nor did he try to sugarcoat his guilt. Many others – some in more senior roles – did far worse and have never even been held to account.

People might argue that he deserved what he got, but they would be ignoring the nuances of his life and the culture of tabloid journalism as it was in his heyday. The newsroom was its own realm, with its own laws and customs. Spend too much time in there and it was easy to forget that the real world had its own laws, too.

He always said, “You live by the sword. You die by the sword”, so I know he wouldn’t mind me airing his dirty laundry now. But the truth is – in my eyes, at least – he cleaned it a long time ago. He stood firmly by the fact he was only ever seeking the truth, he just wasn’t one for finding it legitimately. The pressure he was under to deliver weekly exclusives was crushing. You could argue that he made his bed, but you couldn’t say he didn’t lie in it.

Greg Miskiw was a complicated man, a frustration of contradictions. I have no doubt there are many out there who will not recall him fondly, but in the days since his death, the consolatory emails and calls I have received have painted a picture of a man who fascinated people. A natural raconteur, erudite without pretension. He only spoke when he had something to say. When he chose to switch on his charisma, he was magnetic. Poor health and insomnia threatened to snub out his defiance, but give him some fuel and it was easy enough to fire it up again.

My dad was a restless soul who never found what he was looking for, and all the Famous Grouse in the world couldn’t dull his desire to find it. But he was also fiercely loyal. If I needed a lift from Timbuktu, he’d be there within the hour. He was stalwart in his dedication to my education, and wanted nothing more than for my brother and I to live fearlessly. The only rule he lived his life by was that rules were made to be broken. His one caveat was that we would be “guided by the beacons of his mistakes”.

When the phone hacking scandal broke, he was dubbed the Prince of Darkness. Several years ago, I wrote that this darkness had given way to a faint light. That light only continued to grow brighter, and I will use it to light the beacons.

He is survived by his mother Anna (96), his son Anton, and me. If there’s one consolation, I have no doubt he is happily hunting stories from that newsroom in the sky. We will miss him, warts and all.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog