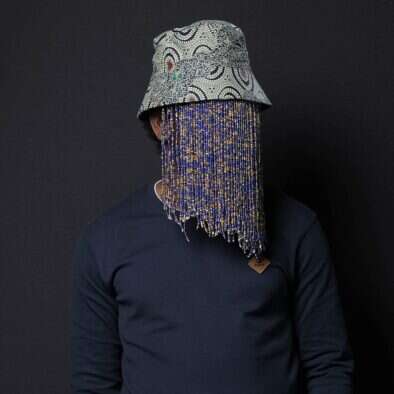

The first thing you need to know about Anas Aremeyaw Anas is that he never shows his face. Whenever he appears in interviews for the press or while filming one of his investigations, Anas can usually be found behind a signature beaded face veil and bucket hat.

While some Press Gazette readers may not know his name, Anas has become one of the most recognisable figures in African journalism, in no small part due to his work in conjunction with a pioneering BBC investigative news programme – BBC Africa Eye, an investigative branch of the BBC World Service.

Together Anas and Africa Eye exposed endemic bribery in Ghanaian football and human harvesting in Malawi. Indeed, from government massacres in Cameroon and Kenyan child trafficking to Nigerian organised crime and tracking jihadists in Mozambique, there are few issues the programme has shied away from in its four-year run.

Aired across 37 African TV channels, Africa Eye nets nearly five million TV viewers a week, has won 27 international awards and has been nominated for the Emmys every year since launching four years ago this month. Its investigations have also gained some 73 million views on Youtube in that time. Vera Kwakofi, the show’s senior commissioning editor, even says that “it’s not a brag to say we’ve changed the face of journalism on the continent of Africa forever”.

For editor Tom Watson, one of the programme’s first hires, the main thing that sets it apart from other foreign reporting is its rejection of “parachute journalism”. The kind of journalism, he says, that sees foreign reporters arriving in a country in the midst of a war, famine, coup or some other crisis, briefly becoming an expert on the place and its history, before subsequently flying away.

“My perceptions of Africa used to be framed by things like Live Aid and parachute journalism, which I think was summed up in a front cover of The Economist in 2017, where it described Africa as ‘The Hopeless Continent’,” he tells Press Gazette. “And I remember not even leaving in the airport on my first trip to Africa and realising that was not a fair representation. It’s a place that is just bursting with journalistic talent.”

‘It’s not the old BBC’

Instead of being run from London, Africa Eye’s investigations are led by a network of hundreds of African journalists working with and for Africa Eye across the continent, including teams in Nairobi, Kenya and Freetown, Sierra Leone. Its UK operation is slim, with fewer than ten dedicated staff in London, Watson says. While the central team helps edit pieces, train local journalists and provide funding and an international platform, the vast majority of filming, editing, producing and presenting is done by their African partners.

It was that approach that first appealed to journalists like Anas, who says: “It’s not the old BBC that we know… We are tired of having people being flown in, journalists who come and have no idea about how things are.

“The African story ought to be told by Africans because we know it so much better. There are places here that you can never go, but I can easily go. There are places in the UK that I can never go to, but you can. So why would you want to come here and tell my story?”

Anas Aremeyaw Anas. Picture: Wikimedia Commons/Reka Nyari

By partnering so closely with locals, the team says it gives Africa Eye access to stories few other foreign outlets even come close to investigating. “In the early days when we were doing our research, we’d fly out and we go to the slums of Nairobi or Kampala and buy a load of beers and get 20 or 30 guys together and say: What do you want to see investigated? What do you care about?,” Watson says. “From that first trip, we probably got our first half a dozen films.”

‘It doesn’t matter if they’re a trained journalist’

That extends to the journalists themselves. Watson explains that the team regularly has non-journalists or fixers not just sharing tips but actually reporting, filming and presenting programmes. Africa Eye then trains and supports them afterwards if they want to continue working as a journalist.

“There’s always a premium on having a person with skin in the game… When we set up Africa Eye, the easiest thing in the world would be to go to the local correspondents’ club, and work with established names,” he says. “But for us, it doesn’t matter if they’re a trained journalist or not.”

Watson explains that one undercover investigation into a systemic culture of teachers forcing female students to trade sex for grades at west African universities was presented by a reporter who had been a victim of it herself. An exposé into endemic child kidnap and trafficking in Kenya heavily featured the market trader who first brought the story to Africa Eye’s attention, who has since continued working with the group on its reporting.

It’s a stark contrast to a lot of conventional foreign reporting, where local journalists are usually restricted to supporting foreign reporters as “fixers”. But as CNN senior international correspondent Sam Kiley once put it: “Any nitwit, and I am living proof, can be a ‘war correspondent’ if they are lucky enough to come across a great fixer.”

Breaking barriers to entry

In breaking with that tradition, Africa Eye has helped remove some of the barriers to entry in an industry that Kwakofi says has always been an “elite profession” on the African continent for those with the right education and media connections.

The other thing that makes Africa Eye different is the sheer breadth of its reporting. When it was first founded the aim was to experiment with new formats, and the show’s initial team was deliberately recruited for their diverse specialisms – Watson was brought in due to his expertise in hostile environment reporting, for example.

Instalments of Africa Eye can vary in length from ten minutes to nearly an hour, while the type of reporting it does can be anything from the kind of in-depth undercover investigations that Anas specialises in, to the open-source investigations that have won particular acclaim. In 2018, the team used the shape of a mountain ridge, the size of shadows and mumbled dialogue to identify the time and location of a massacre of women and children committed by Cameroonian soldiers, as well as the names of the soldiers responsible.

According to Kwakofi, Africa is the perfect place to use those OSINT tools. The population is the youngest on average on the planet with a median age of 20, and smartphone ownership and social media use are both high. In addition there can be many limits on the freedom of the domestic press, meaning big events are often only fully documented on social media.

“It made sense for us to tap into that,” Kwakofi explains. “To use the stories that were already being chronicled by the people of Africa to tell the stories of the people of Africa.”

Africa Eye’s work is having an impact, including bans on the production of codeine in Nigeria and Ghana, the shutdown of abusive drug treatment centres, a national task force established to investigate child trafficking, an official reprimand for a once “untouchable” national TV icon, and a slew of criminal prosecutions across the years.

One investigation into corruption in Ghanaian football that captured almost 100 match officials taking bribes on film led to the suspension of the football league in Ghana, the suspension of more than 50 match officials, and the firing of FIFA’s then-second-in-command for African football.

There is now funding in place from the BBC and the Foreign Office, which helps fund the BBC World Service, for similar investigations units in two countries which cannot yet be disclosed.

However, Kwakofi notes: “It takes a lot of funding to do what we do. So we often have to go back to the bosses and beg for money.”

Africa Eye journalists put their lives on the line

Other than funding, one of the biggest challenges faced at Africa Eye is safety. More than 200 journalists have been killed in Africa since 1992, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists, and the kind of work Africa Eye does means reporters are in the firing line.

Not long after the investigation into Ghanaian football was aired, one of Anas’ lead undercover reporters for the story Ahmed Hussein-Suale had his face and name publicised by a politician opposed to the investigation on live television, with a call for retaliation. The next year, Hussein-Suale was shot and murdered by unknown assailants.

While reporting undercover on a string of killings done to harvest human organs and body parts for ritual magic in Malawi, Anas and his team were almost killed by a crowd of vigilantes – but he seems numb about it now. “It won’t be the first time my life was at risk, and it won’t be the last time.”

Watson and Kwakofi tell Press Gazette that while the BBC takes as many precautions as it can with its work to keep reporters out of harm’s way, not every risk can be ameliorated given the serious, often dangerous, issues Africa Eye reports on.

They also admit that for all its popularity the show has struggled to reach outside of the English-speaking parts of Africa. The team tells me one of its biggest strategic goals for the coming year is to penetrate into French-speaking countries with more on the ground reporting, as well as more hostile environment reporting in hard-to-reach regions.

But the issue of languages does underline something wider about Africa Eye: Is it possible to report on an entire diverse continent properly, or does it risk turning a landmass of 1.3 billion people into one homogenous block?

“For me, when I look at Africa I see a continental story,” says Anas. “No matter how we fight to bring relative peace in Ghana, if our neighbours like Togo or Nigeria are unsafe we are equally unsafe… It makes us see that the problems you have are not very different from mine.”

The long-term goal of the programme is, in a way, to make itself redundant. Watson says: “Lots of Africa Eyes spread all across Africa, with there being no need to do anything in London because our knowledge has been passed on.”

Picture: BBC Africa Eye

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog