Photojournalist Anton Hammerl was the kind of person everyone noticed when he entered a room. “He had a certain presence about him… He was very, very kind. Full of cheeky, wicked humour at times,” says his widow Penny Sukhraj-Hammerl.

“He was someone that was full of life, and he was someone that had a very specific eye, and not just in terms of the photograph, but for an eye for art and capturing moments.”

In 2011, Hammerl, who first became a photojournalist after witnessing the injustice of apartheid-era South Africa while doing national service (he had South African and Austrian citizenship), went to Libya to report on the growing revolution against the then-government of Muammar Gaddafi.

While following rebel troops in the desert near the town of Brega, Hammerl (pictured) and three other journalists were ambushed by government troops. Hammerl was fatally shot and left in the desert while the other three were captured and taken away.

Gaddafi’s forces had told Hammerl’s Surrey-based family he was alive and safe but was in detention. It would be another 44 days before they would learn of his death.

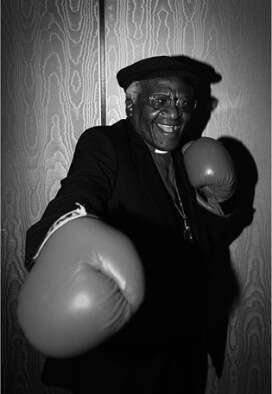

One of Hammerl’s photos, of Desmond Tutu. Picture: Penny Sukhraj-Hammerl

“It’s not been easy. And the trauma is something we’ve all felt,” Sukhraj-Hammerl tells Press Gazette 11 years on. “There was a vacuum in our lives because of losing him.”

The next few months and years were a flurry of Freedom of Information requests and campaigns, pleas to governments for help (both in the UK and South Africa) and fact-finding visits by his friends and colleagues to Libya – including James Foley, a US journalist who was with Hammerl at the time of his shooting and who was himself captured and killed by IS in Syria in 2014.

Mostly, their efforts led to little new information, with Sukhraj-Hammerl particularly critical of the South African government. There was talk of a mass grave where his body may be, but little concrete leads for the family or friends to follow.

By 2013, having found no answers, Sukhraj-Hammerl said she couldn’t continue campaigning at the rate she was given her job as a journalist herself and raising two children, the youngest of whom was born just eight weeks before Hammerl’s death.

Then in 2016, she received an unmarked package. In it, was her husband’s South African passport – the very one he had used to get into Libya. Still, as Sukhraj-Hammerl explains it, in pristine condition. For the past few years, it had been in the hands of the South African government, with the full knowledge of the officials who had been ignoring Sukhraj-Hammerl’s requests for answers over the last five years.

The circumstances of how exactly the passport ended up in their hands are shrouded in mystery. Partly because the South African government has refused to acknowledge how it got its hands on it and partly because Sukhraj-Hammerl can only reveal so much information on the record about how she received the passport to protect the person who leaked it to her.

But it proves that the South African government knew something about Hammerl’s fate that in the years since his death it refused to share, despite a slew of questions and FoI requests.

Anton Hammerl previously photographed soldiers of the Lords Resistance Army, led by the infamous Joesph Kony. Picture: Penny Sukhraj-Hammerl

“We’ve had absolutely no closure. We don’t have a grave to go to. I don’t have anything to take my kids to,” Sukhraj-Hammerl explains. “That’s all we want. We just want the truth.”

It isn’t just the South African government that has refused to help. Despite Hammerl living in the UK for years and raising a family here, Foreign Office minister James Cleverly refused in parliament to exert any pressure in the case, claiming it was the responsibility of the South African or Austrian governments of which Hammerl was a citizen to offer help.

More than 400 journalists have either been killed or gone missing in the line of duty between 2016 and 2021, according to Reporters Without Borders. Sukhraj-Hammerl fears that despite the risks taken on by journalists, her husband’s case proves that reporters are not afforded the same protection given to other high-risk professions.

“All of these governments sign up to these global human rights protocols and they’re very noble and amazing when it comes to talking the talk but when it comes to walking the walk it falls completely flat,” she says. “In the meantime, the killing of journalists with impunity just goes on and on and on.”

She hopes her campaign won’t just bring her family answers, but force governments to make more concrete commitments to protecting journalists.

“If the law does change to give the government a responsibility to investigate, find out what happened and bring journalists’ bodies home that would be something we would be proud of,” she says. “It would mean Anton’s death wouldn’t have been entirely in vain.”

Picture: Penny Sukhraj-Hammerl

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog