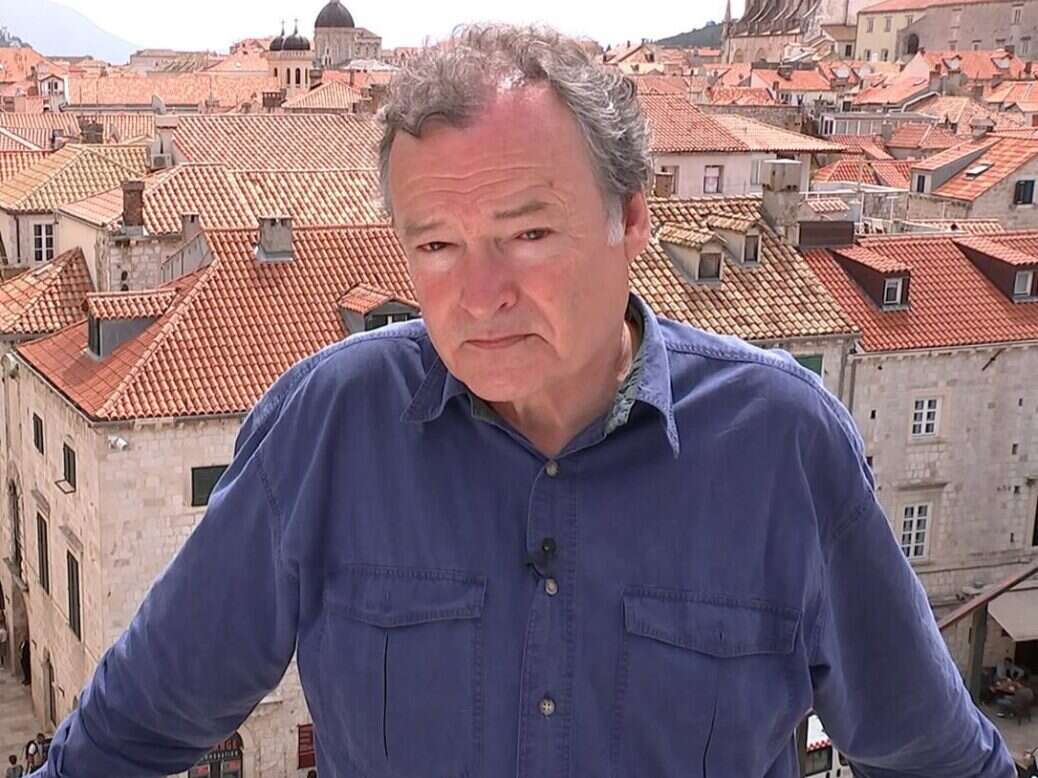

Journalism is said to be the first draft of history. But the account by ITN’s Paul Davies of the siege of Dubrovnic in 1991 is the only draft which history students in the town itself are taught to trust.

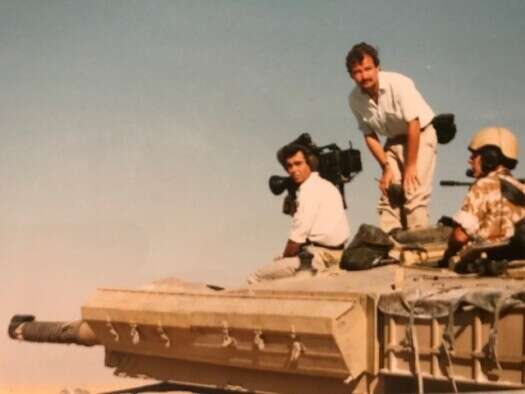

Davies, who retired last month, also reported from the 1984 bombing of the Conservative Party conference at Brighton’s Grand Hotel which killed five. His team were the only British journalists in Bucharest in 1989 when the Ceaușescu regime fell and was embedded with the British Army during the first Gulf War two years later.

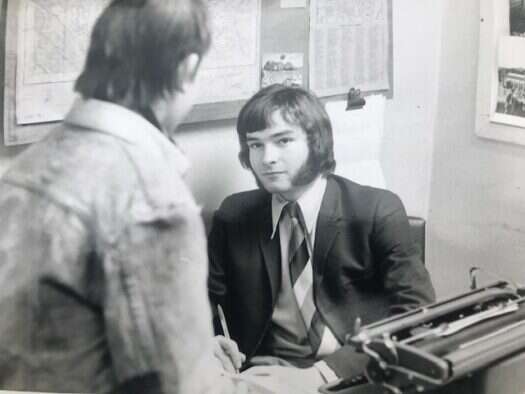

In 51 years in journalism — 39 of which were spent with ITN — Davies went from an apprenticeship with Merseyside’s Southport Visiter newspaper group to a career which has earned him Royal Television Society Awards, Golden Nymphs, a BAFTA and an OBE.

Press Gazette caught up with Davies in the wake of what he called “a rather emotional but very enjoyable leaving party” to talk about his career and his thoughts on the industry.

‘I lost one of my very, very best friends… what happened with him — to him — had a huge impact at ITN’

Asked if he had noticed changes to international reporting since he started out, Davies said: “Yes, huge. That sort of frontline, eyewitness reporting has changed dramatically and most of the change has come quite recently.”

Some of that change has been brought on by technology, which “allows you to do some things that you didn’t used to do. And that can be a huge benefit, obviously. But in some ways it can be a drawback as well, certainly from the more adventurous side of it.

“The days of setting off on a mission and sort of having one last phone call to the newsdesk — ‘I might be some time, let’s see what we’re going to find, we’ll be out of touch for a week or so and see how it goes’ — those days are gone.”

Davies in Saudi Arabia during the first Gulf War (Photo: Paul Davies)

Everyone has a camera now, too. “That’s changed things, and the sort of stories people get sent on, or whether or not they’d actually be sent on them. These days they could just rely on pictures that are appearing on various forms of social media.

“The thing that’s changed it most of all, as far as I’m concerned, is the risk element, and the averse nature of the industry.

“We’ve all got firsthand experience of losing people. I lost one of my very, very best friends, Terry Lloyd, in the last Gulf War [2003], and I know what happened with him — to him — had a huge impact at ITN.

“Managers of news organisations found themselves in situations where they were attending funerals, they were attending inquests. And you know, they were having to ask themselves the most searching of questions as to when and where they would deploy when the next frontline situation happened.

“I think the result of that is plain to see that there is nothing like as much of the frontline, right in the heart of it news reporting as there was a relatively short time ago.”

Had western viewers suffered for that?

“Yeah, I think, suffering through not having your own person there. There are alternative ways of illustrating, finding out what’s happening, but they’re never going to quite compare with having your person there.

“You do tend to have an awful lot more images that are coming out from people who might have reason to side with one party… and therefore you hear phrases often repeated that, ‘We can’t verify this’, you know, lots of ‘We understand that…’, and ‘To the best of our knowledge…’

“But it’s quite often the only source that’s available, and of course you’re going to use it.”

‘The people there seem to have decided… that we played a massive part in Dubrovnik not receiving even worse damage’

During the 1989 Romanian revolution he spent Christmas camped out for days on the floors of the besieged Bucharest Television Centre — which, as well as being the only place he could broadcast from, had become a headquarters for the uprising.

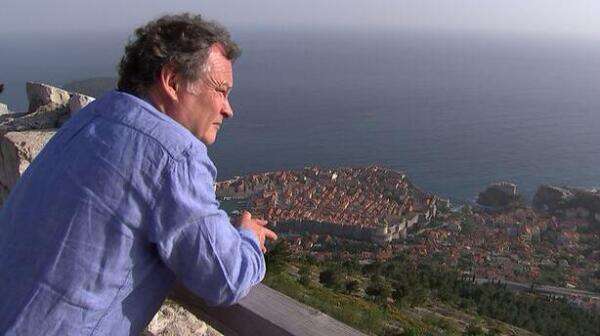

Davies was again on hand during the siege of Dubrovnik; being the only crew of television journalists in the city as the bombardments from the Yugoslav army stepped up.

Davies broadcast from the local television station until the Yugoslavian air force bombed it. After that “we smuggled our final reports out… in speedboats going down the coast that were leaving overnight” — until those too were “shot up”.

When ITN’s stories from the height of the shelling finally escaped the blockade, “it was huge” – Davies says.

“It was the first evidence of what was really happening that reached the outside world. And the bombardment stopped. There was a ceasefire. And the good people of Dubrovnik have decided that that was not a coincidence at all, that pressure was brought to bear on Milošević from Washington, Moscow, various other places”.

Davies was called to testify at Milosevic’s trial for genocide in front of the International Court of Justice, at which the nationalist leader presented his own defence.

“He’d take any answer that he didn’t agree with and he would ask the same question again and again… The Dutch would intervene and say ‘I do think Mr Davies has answered this question quite a few times.’

“It was quite an experience though. Face to face in a courtroom, and being grilled, by a man who was obviously right at the heart of that story that dominated so many years. A man with a fierce reputation, and there he was doing his best to destroy you and the various pieces of work that you produced being included as part of the prosecution.

“If you ever want an example of why even in the most stressful conditions of war reporting, you should think about every word you use, and very, very carefully choose the images in your report: the fact that you might end up having virtually frame by frame match reports that you put together under those incredibly pressured circumstances taken to pieces, put under the microscope in a court — and not just any old court”.

Milosevic “tried to completely undermine the truth of that report. And he failed and I was just so, so pleased… that we’d spent that time doing that because it stood the test of the years and the tests of the court interrogation”.

Davies visited Dubrovnik in 2019 for an ITV programme about how the city has fared since: “Possibly the nicest, nicest thing of all,” he told Press Gazette, “was we went into a school of sixth formers… to find out that they knew virtually every single report I’d ever sent, that they’d been taught those reports as their own history in school.

“And they told us this was the only material you could rely on being truthful because everything else you’d see would be propaganda, and this was the truth. And that is lovely. That is a legacy.”

Davies as an apprentice reporter with the Southport Visitor group in 1971 (Photo: Paul Davies)

‘Highlighting that and trying to improve it seemed the natural and right thing to do’

In the latter half of his career, Davies has worked largely in the UK, covering stories including the 7/7 bombings, the murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby, and the fortunes of returned veterans.

“I wanted to have some sort of a family life and it was quite clear that it was going to be difficult to do that if I continued being out of the country for some months of the year, and on frontlines in particular, being blown off my feet [something that Davies says happened to him twice] and that sort of thing.”

He ended up working on veterans’ issues “like everything else, sort of by mistake. A little random, but there was a sort of a feeling that having spent a lot of time with the military, even in uniform… I always think I had quite the affinity, particularly with the older veterans.

“When it became clear that quite a few of them have had very difficult times despite all of their contribution, then highlighting that and trying to improve it seemed the natural and right thing to do.”

Reporting horror

Press Gazette asked Davies what had surprised him the most in his career.

“The most shocking thing has been man’s ability to turn on himself I suppose — to turn on fellow man. I don’t think there’s been anything much worse than the ethnic cleansing. By the time I went to places like Srebrenica I had thought I had pretty much seen it all and experienced it all, but I wasn’t ready for that.

“I was with [current Conservative MP] Colonel Bob Stewart when we discovered the massacre at a place called Ahmići [in 1993], which is not far outside Sarajevo.

“The Bosnian Croat militia had gone into the village, separated the men and boys from the women, shot most of the males, herded the women and children into the basements of houses, and then set them on fire.

“When we arrived there, we walked into a basement and it took a few seconds to realise that the ashes, and what we were walking into, and at first what we were walking on, was the remains of women and children. And that’s just about the most dreadful experience of all, I think.

“Try and put that into three or four minutes of a television news bulletin.”

Press Gazette asked Davies how he conveyed such deep horror to distant audiences.

“With huge difficulty… you look back at the piece that you recorded at the scene and whether you knew it or not, you could tell that you were affected by it.

“You know, there is, and was, and always will be a huge debate about how much you can show people of what’s happening… But there was a feeling as the Bosnia situation got worse and worse, that by doing that [reporting too cautiously] we might not have shown the world just exactly how appalling the things that were happening there were.”

‘Until we can get back to a situation where reporters… can get to the front line where things are happening, then that form of journalism isn’t going to be what it was’

Asked what he sees in the future for international reporting, Davies said: “I would love to think that we can find a way to get some very, very talented correspondents back in the places where they need to be. And I hope technology can help with that.

“But in the short term, until this whole nightmare of correspondents becoming targets, being kidnapped, passed on from kidnappers to groups who use them for propaganda… until that threat goes away, then it’s very hard to see it returning to the old style of international correspondence.

“I’m tempted to criticise why we aren’t doing more of that sort of work, but there are massive issues.

“If you are the head of foreign news of either ITV News or the BBC, and you’ve attended the funerals and stood with the families of correspondents who’ve lost their lives working for you. It’s going to have a huge impact on you. And I can understand why things are different.

“But until we can get back to a situation where reporters with no axe to grind — completely independent eyewitnesses — can get to the front line where things are happening, then that form of journalism isn’t going to be what it was. And the world will suffer as a result.”

Pictures: ITV News, Paul Davies

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog