The BBC’s youngest network news correspondent has spoken about the moments the responsibility of telling stories about the human cost of the Covid-19 pandemic “sunk in”.

Rianna Croxford, named New Journalist of the Year at Press Gazette’s British Journalism Awards in December, had a rollercoaster year in which she was appointed BBC News community affairs correspondent, worked on a harrowing Panorama investigation, and was targeted with racist abuse after accusations in the press of biased and agenda-driven journalism.

The awards judges said: “Rianna is a great investigative journalist who constantly reports stories that often go overlooked at the BBC.”

Croxford, 26, started as community affairs correspondent as the UK went into lockdown in March and said although it was her “dream role” it was probably not the dream timing.

But she said despite a “tough year” she was “really proud of the conversations and some of the change that we’ve managed to have this year” having helped to drive coverage of the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on ethnic minority communities during the early part of the pandemic.

Croxford revealed in June that a black doctor had not led a review into the impact of Covid-19 on ethnic minorities, despite a previous Government announcement. She also revealed that a second report containing measures to protect these communities from coronavirus had been drawn up but not yet published. It was released within days of her report.

She told Press Gazette this was the moment the impact that public interest journalism can have “sunk in” for her and acted as “quite a big turning point”.

[Read more: Full list of British Journalism Awards winners as FT’s Dan McCrum crowned journalist of the year for Wirecard investigation]

She later experienced a similar feeling after spending three months investigating whether all lines of inquiry were pursued after the death from Covid-19 of transport worker Belly Mujinga for Panorama following reports she had been coughed at and spat on by a customer.

Croxford said she did not expect to find the investigation as hard as she did: speaking to Mujinga’s husband and friend made the human cost of the virus and “the responsibility that comes with that and making sure that people’s stories are told fairly accurately and as close to their truth and experience as possible” really hit home.

“That was a big, big wake up call,” she said.

In June, Croxford woke up to find a picture of herself taking up half a page in the Mail on Sunday next to the headline: “BBC accused by Minister of fanning racial tensions over Covid AND Black Lives Matter.”

Then, in July, she was the subject of Guido Fawkes and Daily Mail stories calling her a biased “Corbynista correspondent” because of tweets she sent while at university, while the following month she was named in a letter from MPs to the BBC’s new director-general Tim Davie claiming there is a “distinct lack of impartiality in BBC reporting and commentary”.

These stories led to an influx of racist abuse against Croxford and she said: “I remember sitting there in my room thinking I haven’t even been in the industry that long, I don’t know how I somehow developed this weird reputation as being the most biased employee even though it’s unsubstantiated and not really rooted in any evidence.

“People can make their own conclusions as to where they think those sorts of attacks come from.”

Impact of Black Lives Matter movement on newsrooms

Croxford was one of only four black journalists to ask a question during the Government’s more than 90 press briefings which were held daily between March and June.

She was the first in her family to go to university, getting into journalism after studying at Cambridge on a bursary and then for her NCTJ diploma with support from the Journalism Diversity Fund.

Croxford said she was among a number of BBC journalists who were keen to shake things up and give a voice to under represented groups, adding: “There’s been such distrust in [certain] communities at how they felt represented in the media, really having people who they feel are objective, impartial and sympathetic has helped in being heard in that way.

“It really taps to an underserved audience or community and can bring a new audience to your to your platform… and rebuild trust with communities.”

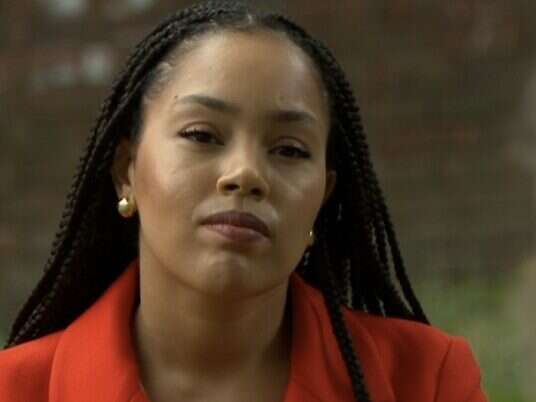

BBC correspondent Rianna Croxford. Picture: BBC

It should not have taken the death of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter conversation this year to ignite the debate on diversity in journalism and give a platform for more journalists of colour, she said.

But she said the most important thing is for bosses is to listen and be open to new ideas, as well as ensure that journalists of colour are not only allowed to report on race.

[Read more: Warning that tackling newsroom diversity by starting at the bottom can look like ‘window dressing’]

“It was very clear during the pandemic that I wasn’t just looking at the impact on those communities, but also about policy, I did stories and investigations about education, and politics, and other areas,” she said.

“I think being open to seeing journalists in different roles, and making space and time for that. And I do think there are quite a few editors and people in senior positions particularly at the BBC at the moment who do make that time and are willing to support more junior colleagues.

“There are lots of different people I saw on TV reporting who maybe two years ago would have struggled more.”

Stepping up

Croxford’s own TV break came in late 2018 after she invited herself to a BBC editorial meeting to pitch a story she had been working on with the data team for six months about the ethnicity pay gap at universities.

As she was working in a production role, not on-air, at the time there was a “general feel” that she might not be the best person to tell the story but she advocated for herself with top editors.

“The BBC is such a big place and I was struggling to figure out who to pitch to and I heard there was an editorial meeting that happens a couple of times a week,” she said. “I invited myself along, at the end put my hand up and was like ‘I’ve got a BBC exclusive’ and they just kind of stared at me thinking ‘who is this person who’s come into the room?’.

“I didn’t even sit on the backbenches. I had no idea there was some unspoken hierarchy about where you were meant to sit. I just sat at the main table and arrived early. It got commissioned on the spot.”

Croxford, who is now a BBC News correspondent based in the UK investigations team, said her experience seemed to have helped other junior colleagues take ownership of their stories instead of letting them always pass to more experienced correspondents.

“I think some of us made the point at the time that if you do that then you sort of sever the tie you have with the audience and people who might approach you with stories, who might not approach your other colleagues because of trust or personal reasons whether it be not being able to see someone they connect with.”

She added: “This summer you could see so many different people on air, not all of whom are official correspondents and it’s been really, really great to see… People feel like they have the confidence now.”

Picture: BBC

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog