The Guardian and Sony Pictures Entertainment have agreed a deal that grants Sony exclusive first rights to adapt Guardian journalism into film and television documentaries and dramas.

News of the agreement, which covers both The Guardian’s ongoing work and its 200-year back catalogue, was met online with surprise and amusement.

Several commentators asked what the deal meant for Guardian journalists whose work may be used for future productions, or how factual reports could be copyrighted in the first place.

Most respondents, however, expressed excitement at the prospect of a film series based on the work of columnist Adrian Chiles.

Press Gazette spoke to The Guardian and copyright lawyers to hear why publishers license the rights to their stories to the entertainment industry and what it means for the journalists involved.

How unusual is The Guardian’s first look deal with Sony?

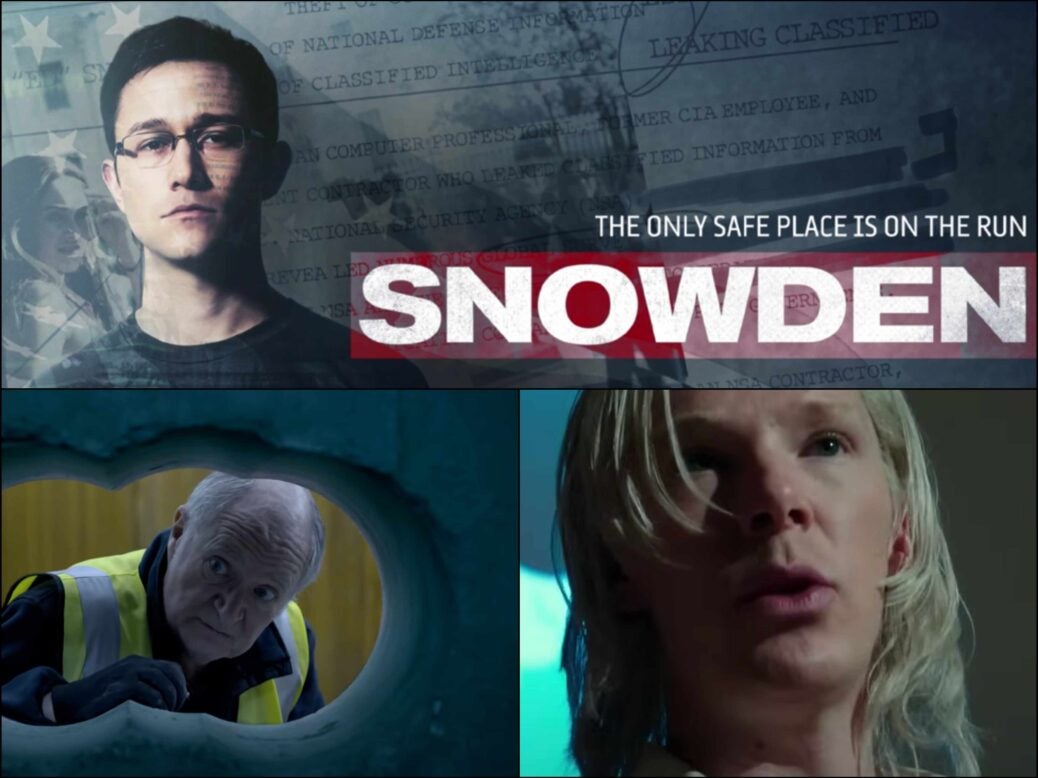

Publishers licensing their stories to production companies is not new: if you have seen Wikileaks thriller The Fifth Estate, 2016’s Snowden or the 2018 Hatton Garden heist film King of Thieves, you have already watched a movie adapted from Guardian journalism.

And The Guardian is far from the only publisher to shop its intellectual property out to the entertainment industry. Tortoise, the “slow news” audio-first publisher behind hit podcasts Sweet Bobby and Hoaxed, signed a first look partnership with Sky Studios last year.

Earlier this year entertainment trade magazine Variety agreed a similar deal with Hearst and Disney’s A+E Networks.

First look deals like these give a studio the opportunity to consider a project before any competitors.

Last year, Netflix released the documentary Skandal! Bringing Down Wirecard, which told the story of the Financial Times journalists who exposed widespread fraud at German financial technology firm Wirecard. This was an unusual case, however, as the newspaper didn’t make any money from the film, feeling it was important to get the story out there.

Indeed, there is a long history of films based on newspaper and magazine articles. Among the results:

- Top Gun (1986) – based on the 1983 California magazine article “Top Guns” by Ehud Yonay

- Argo (2012) – based on the 2007 Wired article, “How the CIA used a fake sci-fi flick to rescue Americans from Tehran” by Joshuah Bearman

- The Bling Ring (2013) – based on the 2010 Vanity Fair article “The suspect wore Louboutins” by Nancy Jo Sales

- Hustlers (2019) – based on the 2015 New York article “The Hustlers at Scores” by Jessica Pressler

- The Fast and the Furious (2001) – based on the 1998 Vibe article “Racer X” by Ken Li.

What rights do journalists have when their stories are dramatised?

The copyright that a journalist retains over their reporting depends on their contract with their publisher. Some news organisations require new staff to hand over the copyright to the stories they write for the outlet when they sign their employment contract.

These contracts are typically private, but a terms and conditions page on the Guardian’s website lays out the rights its contributors have when their work is dramatised or used in documentary making.

The page says The Guardian has the exclusive right “to represent your contribution and agree sales in principle”. But it adds that when The Guardian is approached with an offer from a production house “we will share these details with you along with an offer of equitable terms to reward you and move forward together”.

The newspaper does not hold its journalists’ copyrights forever. Three years after a story is published, its author can write to Guardian News and Media to request the return of licences and rights associated with the work. It appears that those requests will be granted provided no third party has already expressed interest in adapting the work and there are no other, overriding agreements between GNM and the author.

[Adrian Chiles interview: ‘I’m not playing a part here, this is what I really think’]

How can you copyright news in the first place?

Some readers asked how it was possible for a copyright to exist over factual information in the first place.

Mark Nichols and Mark Kramer, two intellectual property solicitors at law firm Potter Clarkson, told Press Gazette that there is a concept within copyright law of “the idea-expression dichotomy”.

Nichols explained: “There’s no copyright in an idea or an event. But there’s copyright in the way that you express that idea or you express what has happened in relation to that event.”

He cited an unsuccessful copyright case brought against The Da Vinci Code publisher Random House in 2006 as an example. The lawsuit was launched by the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, the 1982 work of ostensible non-fiction that first popularised the factually-dubious claims at the heart of the (fictional) Da Vinci Code.

Nichols said: “The court found there was no infringement because you’re quite entitled to both write about the same things because there’s no copyright in the idea – there’s copyright in how you’ve gone out and expressed the idea.”

Why would a news organisation license factual reports to entertainment companies?

The Sony deal is a way for The Guardian to make money from its archive. Guardian director of public policy Matt Rogerson tweeted on Wednesday that it was “great to see companies like Sony Pictures valuing the IP created by world class news organisations”.

Nicole Jackson, The Guardian’s head of audio, told Press Gazette this week that podcasts that involve significant reporting are prime intellectual property for production companies.

“IP has become an avenue for us,” she said, “and there are various series that have gone on to be bought by documentary companies.”

She cited as an example the podcast Can I Tell You a Secret?, which she said “was a – I hate the term true crime – it was a cyber-stalking series that we made. The IP was bought of that, and Netflix have made a two-part documentary that’s being released next year.”

She said Today in Focus mini-series The Division and Searching for the Shadow Man are also being turned into documentaries.

“That is really gratifying as well, that those stories which are really important get kind of another life and hopefully a whole new audience as well,” Jackson said.

Monetisation without too much effort

Potter Clarkson solicitor Kramer said: “I think it’s a very sensible thing for The Guardian to have looked at its portfolio and thought: ‘How do we monetise this without too much effort?’”

Nichols agreed, citing the threat posed to publishers by the rise of generative artificial intelligence: “It’s almost getting ahead of the game in terms of working out how to make money from stuff that might very soon see its value – I would say wrongly – decline…

“If you have people starting to churn out somewhat low-quality pieces about events that have been going on – and then you have Sony saying, ‘We’re doing this with the full backing of The Guardian’s back catalogue and ongoing investigative work’ – it gives them some real reputation and kudos in the area that they may not otherwise have had.”

He also pointed out that the deal was useful in a practical sense for Sony: “With anything breaking – so you can imagine with the Panama Papers for example – it will give them a real element of speed. They’ll be however many weeks or months of investigation ahead of somebody else putting out a movie on the same subject.”

Jonathan Blair, who leads the film and television group at media law firm Simkins, noted that the deal would likely help Sony produce better films than they would be able to if going it alone.

“Often, great insights and informative narratives are not in the public domain but rely upon the in-depth research and unique access that journalists have as a product of their origination,” he said.

“These articles will have separate copyright. It is these articles that shall be the basis of the collaboration and can lead to some fascinating and original films, especially in the factual arena.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog