When was the last time you read about Japanese bondage clubs and ancient Roman poets wanting to make their critics perform fellatio?

If it’s been a while, then you have not been reading the London Review of Books.

“There was a piece somewhere on the internet recently that referred to us as being rather staid and mentioned we had recently opened an issue with a review of a new translation of Catullus,” co-editor Alice Spawls tells me. “In fact, that piece was one of the funniest things we’ve published this year.

“It described Roman poetry through metaphors of Japanese bondage and was very sexy and unexpected.”

Despite running articles that can stretch into the tens of thousands of words, the LRB has gone from being a niche offering to one of the most popular cultural and current affairs magazines in the UK.

The publication proudly boasts on its website that one reader described it as “the best thing about being a human”.

“A lot of people feel they know the character of the paper better than we do. We get told off for any perceived fallings off from perfection,” says Jean McNicol, the magazine’s other co-editor. “People feel part of something… In all sorts of strange places you go you meet somebody who has some encyclopaedic knowledge of the paper, some people are quite obsessed with it.”

And that fanbase isn’t small anymore either. The LRB’s fortnightly print magazine has a circulation of 91,859, according to the most recent ABC figures (95% of which were actively purchased).

'Looking for sustainable, profitable growth'

That’s a 4% increase on the year before and well over double the readership the magazine had 15 years ago. It makes it the fifth best selling title in Press Gazette's news and current affairs ranking, with only The Economist, The Week, Private Eye and Time selling more. The New York Review of Books, the parent publication that helped launch the LRB in 1979, itself had a 2020 circulation of 131,598.

“Looking for sustainable, profitable growth is what underpins our subscription strategy,” says LRB publisher Reneé Doegar, who adds that the magazine saw five years' worth of subscription growth during the pandemic. “In terms of the annual growth over time, it's just been based on really clear data and using really various kinds of sophisticated modelling."

But despite its success, the LRB team often struggle to find the words to define themselves. Each year, in its annual ABC circulation audit the magazine is classified as a general interest literary magazine, the sole publication in that category. Doegar says the group “have the conversation all the time of whether or not we're in the right one”.

It seems a fitting problem for a publication that publishes content that few other outlets would. “I think part of what we would hope is the appeal everywhere is eclecticism. Our diary slot can be anything from someone reporting from a warzone to Alan Bennett listing the best churches he's visited,” says Spawls. “A good example of it might be in the last issue, there's a short piece about using a typewriter. I don't know where else you would read that.”

The LRB list of 15 contributing editors (the title given to regular contributors) covers journalists, professors and Booker Prize-winning authors, including Hilary Mantel, Colm Tóibín and Patricia Lockwood. Over the years, the likes of Alan Bennett, Martin Amis, Christopher Hitchens and Paul Foot have been regular contributors to the magazine.

But it also features unknown writers and journalists, some of whom go on to become household names, and finding the right people to feature is an ongoing challenge.

'The pressure is there to be 24/7'

The magazine’s captivated followers send in hundreds of submissions for each edition – “most of them aren't very good, or very interesting though,” Spawls remarks. “You just have to try lots of people. And some of them work and can end up being a big thing.”

Being fortnighly (like Private Eye) brings its own complications. “You always seem to go to press at the wrong time,” McNicol explains. “Elections always come on the wrong week, the war starts on the wrong day – which actually happened with one of our most recent issues.”

Do they ever want to break from the straitjacket of the fortnightly print cycle? “The pressure is there to be a 24/7 publication,” says Spawls. “But we try to add to the conversation in a way that the quickfire news responses can’t.”

Despite its geographically-weighted name, the LRB is also increasingly a global phenomenon with roughly 44% of its readers coming from the UK, 33% from the US and the remaining 23% from the rest of the world.

That global community has always been part of LRB's DNA according to McNicol, who is herself Scottish. Even in the old LRB office she recalls machines printing out addresses as far away as Vanuatu in indelible black ink.

Her mention of the old office is telling. She and Spawls only took over the editorship of the LRB in January 2021, when LRB co-founder Mary-Kay Wilmers, who edited the publication for more than 30 years, stood down. Later that year, Doegar took over the mantle of publisher from Nicholas Spice, who had been in the role for almost the magazine’s entire 41-year lifespan.

Image: Renee Doegar / The LRB

Both Spawls and McNicol are LRB lifers. Joining in 2011 and 1987 respectively, both spent their entire careers at the magazine working under Wilmers. Doegar stands out as the closest thing to an outsider, having worked for Haymarket Publishing for just over six years before joining the LRB in 2011.

All three speak with an almost sacred reverence for Wilmers and her tenure as editor of the LRB, from her open-mindedness and ability to find new writers to her dedication to constantly searching for articles in the colossal "slush pile" - their name for pitches or un-commissioned articles the publication gets sent.

“Lots of people just don't bother with them. But she was always very keen that we should look at them,” says McNicol. “There are things in the paper that are changing, and I'm not saying it's a statue that can't be altered, but it's definitely just a development of what went before rather than any kind of break.”

While the shadow of Wilmers looms large over the publication, not least because she has stayed on as a consulting editor, that hasn’t meant the organisation hasn’t been going through some big changes recently.

As with many news titles, and society more generally, the pandemic became a catalyst for innovation at the often stubbornly unchanging LRB. Events normally hosted in the LRB bookshop shifted online, book sales moved to a newly launched e-commerce arm (that has since moved on to selling everything from stationery to scarfs) and then there were podcasts.

“We hadn't had a regular podcast until the pandemic. And it sort of fell into place then,” says Spawls. “We had an occasional series of a very good podcast called close readings by Seamus Perry and Mark Ford in which they would look at a particular poet… During the pandemic, we made it more regular, and now we have a podcast after each issue, which talks about a piece in the issue with the writer.”

In some ways, the reverence for Wilmers is no surprise given how much the publication owes her, both figuratively and, as it turns out, literally.

The outlet shies away from discussing its bottom line but was reported by The Times to be £27m in debt to the Wilmers' family trust in 2010, though Wilmers, an heiress to a fortune made in the fur trade, said she had no intention of recouping that debt.

The most recent Company House accounts suggest the company lost £4.6m in 2020, and £3.6m the year before that, though when we asked about those figures Doegar reiterated that “there was no intention to collect that debt”.

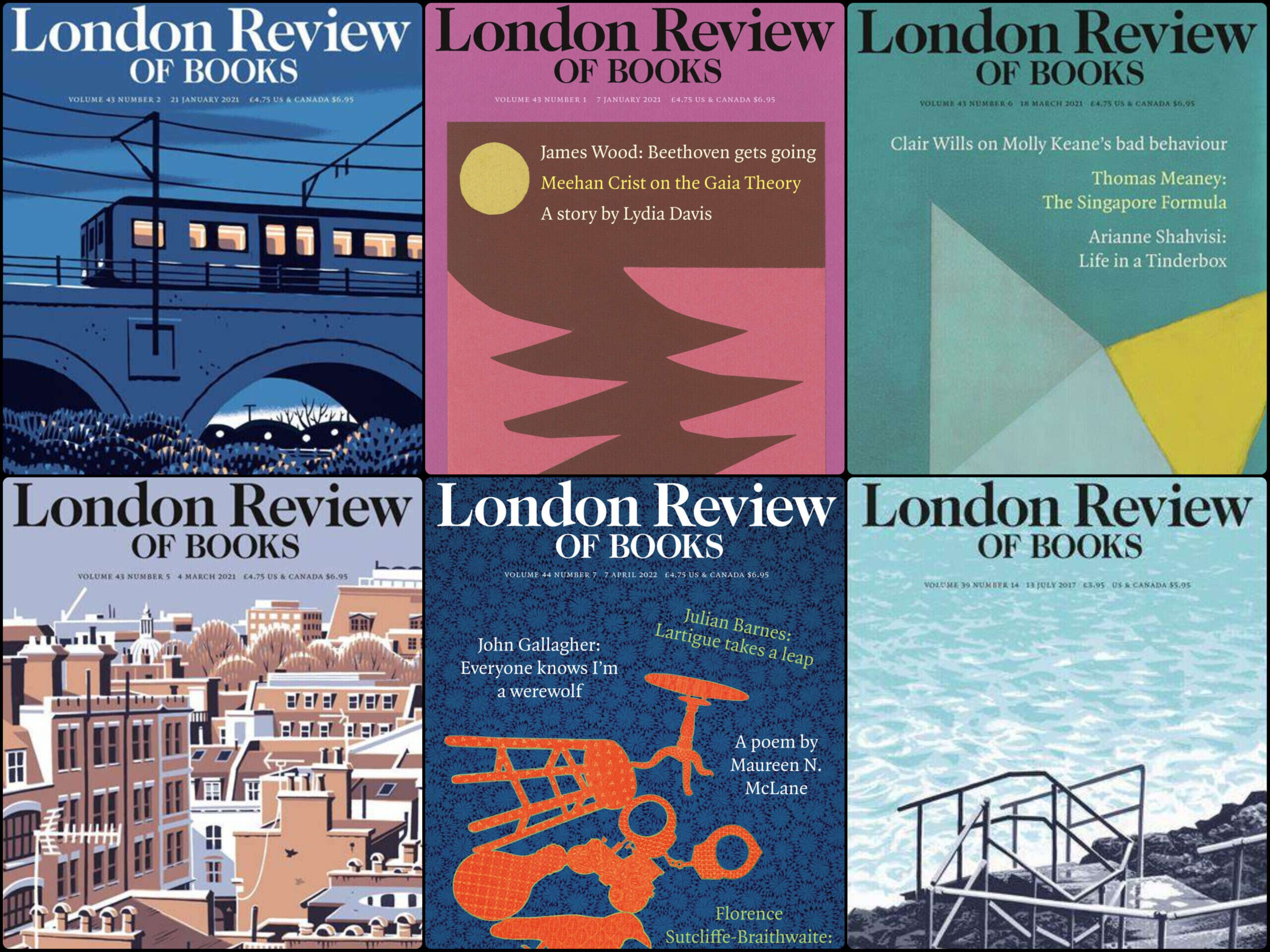

Picture: London Review of Books

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog