Paywalls are plagued by a paradox for publishers.

On one hand, they offer the seductive prospect of secure, recurring revenue from a group of loyal users. On the other hand, they come at the price of reductions in traffic, users and therefore ad revenue.

Introducing digital subscriptions is a big step, especially to products which were previously free. But the choppy seas of the online advertising market have left many news publications struggling to stay afloat.

So, more and more, publishers are switching to paywalls. Confidence is boosted by knowing that the whole industry is moving to this model, and some publications have made a huge success of it.

Done well, a new paywall is a very rewarding and encouraging thing. Seeing the numbers rising day after day is exciting. Extrapolating the growth sometimes leads to the thrilling prospect that initial targets might have been too pessimistic; they’re on-course to be smashed.

However, for many publishers, those giddy early days are short lived. Sign-up rates slow, churn increases and early targets slowly retreat back into the distance. The business of creating and sustaining a growing subscriber base becomes a daily grind.

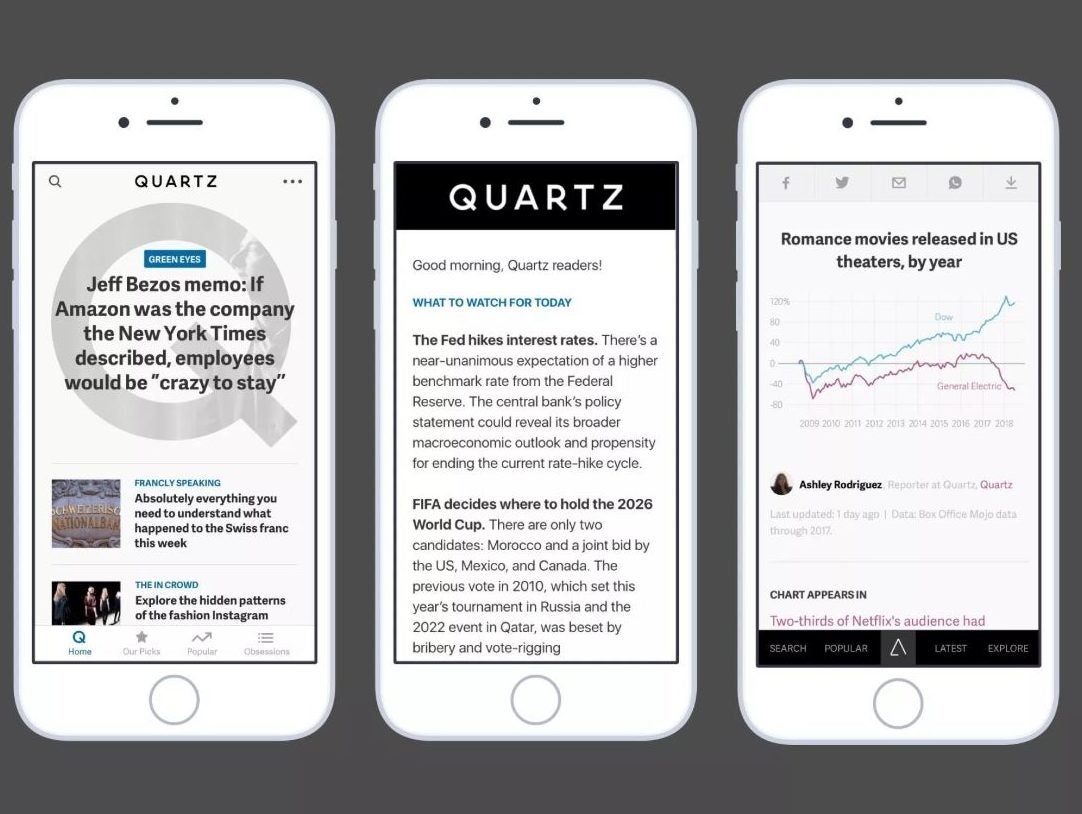

Last week, Quartz threw in the towel, reverting back to a free content model after having spent a couple of years building up a – pretty respectable – 25,000 subscriber base.

Explaining their decision, Quartz’s chief executive Zach Seward offered this telling comment: “Our members have clearly expressed that their number one motivation for paying for a membership is that they love Quartz and want to support the truly global and thoughtful business journalism that we do.”

In other words, some of Quartz’s subscribers aren’t really subscribers at all. They’re not paying to get past the paywall and read a product they consider essential; they’re paying to help keep Quartz in business. Not so much subscribers as supporters, or patrons.

Similar things can be seen in the statistics of publishers. For some, subscribers visit once or twice a month on average, and read one or two items when they do. There’s an alarmingly large cohort of “ghost” subscribers, who pay monthly and never visit at all. They’re clearly not paying for something essential to their daily, or even weekly, habits.

This revelation is good news for Quartz, because it raises the prospect of having their subscriber (now re-cast as ‘membership’) revenue cake whilst also swallowing a high-traffic advertising income as a second helping of dessert.

Similar things work elsewhere: The Guardian, and some others, have generated a meaningful and sustained income from voluntary payments.

But what does it mean for paywalls, when subscribers aren’t really subscribers at all?

The stark truth is that every paywall encounters slowing growth and, eventually, a ceiling on subscribers. For some that ceiling is high, millions of subscribers, and the future is bright. For too many others, like Quartz, it’s not high enough.

Publishers have a cocktail of tricks to keep the numbers rising. Discounts, often over 90%, even up to 98% (or in one case, bizarrely, 100%!) proliferate. Special incentives, metered paywalls, memberships – they’re all aiming to shore-up their subscriber base and traffic.

Perhaps, though, it’s time to ask whether subscriptions are the right model for the news industry at all.

The market is saturated, yet 92% of the UK population don’t pay for a single digital news product. Nearly every would-be reader of nearly every publication will never subscribe. There are no successful paid digital news products addressing the mass market. As the cost-of living crisis bites, subscriptions are high on the savings list for many families, as the recent reduction in customers for Netflix shows.

The simple truth is that asking people to pay too much for something they don’t really want doesn’t work. Relying on the charitable instincts of a small section of the audience is not a business model which an entire sector can rely on. Hoping people don’t notice they’re still paying for something they never use is not a long-term strategy.

The news industry is running the risk that stagnation will turn into an accelerated collapse, as weakened foundations are further undermined by global economic stress.

So, now is the moment for the industry to turn its optimistic sights in a different direction. We should start to ask what else we can do to persuade more of the audience – which is massive – to part with their money.

Let’s start by dropping the demand that users continuously pay for something they only occasionally want to read. Let’s get rid of the concept of churn, and focus on frequency (and dormancy) instead. Which means, let’s focus on making the products, as they once were, unmissable.

Newspapers used to cost a few pence every day, and sold millions of copies, every single day. We still have those millions of readers, what we badly need is to bring back those few pence. Spent every day, by millions of people, they add up.

Perhaps we can find our future inspiration in some of the lessons from our glorious past.

Dominic Young is a news industry strategist and commentator. He previously held a number of strategic and operational roles at Newscorp and has initiated and run a number of industry-level initatives and organisations. He is currently CEO of Axate, a company he founded to create a new network and better business models for media and its consumers.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog