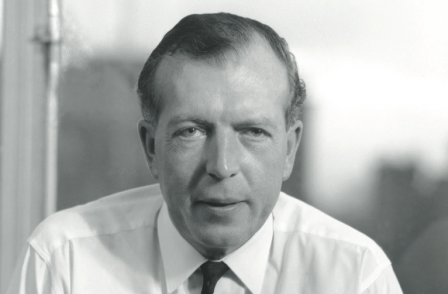

Former Sunday Express journalist Graham Lord writes about his experience of working under legendary editor John Junor after joining the title straight out of university in the early 1960s:

Despite my lowly position on the paper, my wife Jane and I were invited regularly to join JJ and his cronies on his sailing boat, which he kept in the Hamble River, and to spend weekends with his wife, Pam, and family at his house near Dorking, Wellpools Farm, where he would ply me with fat, late-night glasses of calvados until I could hardly keep my eyes open. It was not until several weeks later that I discovered the reason: Jane told me that she couldn’t stand those weekends any more because JJ would grope her at every opportunity and had once chased her along a corridor. The endless huge glasses of calvados had been the old goat’s attempt to knock me out so that he could ravish my wife. We never accepted another invitation to stay.

I think JJ propositioned the wives of almost every member of his staff. During one Sunday Express cricket match against his Surrey village, Charlwood, on a blazing summer day, the very good-looking wife of one of our sports writers was foolish enough to remark how hot it was. Junor pounced. He kept insisting that she should go with him to Wellpools for a cold shower, and he was so persistent that eventually she agreed. As she stepped out of the shower she saw him standing in the doorway wearing nothing but underpants and a leer. “Oh, John!” she said. “We’ve been such good friends for so long, let’s not spoil it.” He crept red-faced out of the room and she escaped unsullied.

Even though JJ looked like a seedy gargoyle as he grew older he leered at almost every woman he met, propositioned many, and instructed his showbiz correspondent, Roderick Mann, to play the pimp by regularly persuading pretty young actresses to meet him for cosy dinners. On one such occasion he told Roddy to pay the bill and claim the cost on his Sunday Express expenses. He had long affairs with at least two Sunday Express secretaries, one of them a sweet but plain girl whom he promised after he was knighted that he would divorce Pam, marry her and make her Lady Junor. The poor girl believed him and was devastated when he dumped her.

She gave birth to a son and claimed that the father was a middle-aged Sunday Telegraph journalist, but some of us suspected that the child was in fact JJ’s. He had another affair with a young married reporter who became pregnant and was convinced that the baby was Junor’s. He refused to believe it and the affair ended with anger and recriminations.

A memorable JJ cock-up occurred in January 1968, when he sent me to interview the tiny, toothy, pop-eyed, chain-smoking, Scotch-swigging, fast-talking, forty-three-year-old American writer James Baldwin. When I delivered the article there was a long, ominous silence from the editor’s bunker. Eventually JJ called me in.

“Baldwin,” he growled. “He’s black.”

“Yes.”

“He is also a homosexual.”

“Yes.”

“I didnae ken that he is black.”

“Ah.”

“Nor was I aware that he is a queer.”

I gathered my courage. “Well, that’s the whole point of Baldwin,” I said. “All his books are about being black and homosexual.”

“Ye should hae warrrned me,” he muttered. “The Sunday Express is a wholesome family newspaper. The Sunday Express disnae publicise black perrrverrrts.”

The article never appeared.

He encouraged me to apply to succeed him as Editor of the Sunday Express when he decided to retire in 1985, at the age of sixty-one, and then – when the owner of the Express, Lord Matthews, duly agreed to give me the job – JJ deliberately prevented me getting it.

Sir Max Hastings, who was editor of The Daily Telegraph from 1986 to 1995, described JJ in his Fleet Street memoir Editor as being “by common consent one of the most disagreeable men in Britain” (and he called him “reptilian” in his autobiography Did You Really Shoot the Television?), and an ex-editor of The Sunday Telegraph, Sir Peregrine Worsthorne, described Junor in the New Statesman as “a world-class legendary monster . . . a deeply unpleasant, philistine and hypocritical man.”

JJ’s delightful daughter, Penny, who became a good friend of mine and a glamorous TV presenter and biographer, makes it clear in her brave, poignant, brutally honest memoir of her father, Home Truths, that he was indeed a monster.

JJ was a bigot who instructed his staff never to trust a man who smoked a pipe or wore a beard, hat or suede shoes. He believed that Aids was a fair punishment for buggery. He announced that “only poofs drink rosé.” One fragile young feature writer, Paul Pickering, was mortified when JJ decided he should no longer write his ‘Under 21’ page for young people.

“But you’ve often told me how good it is,” protested Paul.

“Aye, laddie,” said JJ. “Sometimes it’s brrulliant and sometimes it’s piss-poor, and what I want is consistent mediocrity.”

At his peak JJ was himself a brilliantly curmudgeonly columnist who attacked his targets with a series of vividly contemptuous catchphrases: “Pass the sick-bag, Alice”; “I do not know but I think we should be told”; “I’d rather play the piccolo in a pissoir.”

But he came to care more about his column and his own reputation than he did about the paper, which lost 2.5m copies in sales during his 32 years as editor – 78,000 a year, an astonishing long-term collapse in circulation that would surely have earned any other editor the sack.

He was also a blatant hypocrite who told me that “no decent journalist should ever accept a bauble from a politician” yet proceeded to accept a knighthood from Maggie Thatcher.

He sneered at journalists who accepted free trips, accusing them of corruption, yet he accepted with relish numerous free flights and holidays provided by his golfing friend Sir Adam Thomson, the Scottish chairman of British Caledonian Airways.

He told me that “no honest journalist ever made much money” but when he died in 1997 left more than £2m – the equivalent of nearly £3m in 2011. Pass the sick-bag, Alice, indeed.

This is extracted from LORD’S LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: 100 Legends of the 20th Century by Graham Lord which is available as an ebook from www.amazon.co.uk or as a hardback or paperback only from www.fernhillbooks.co.uk.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog