Times chief reporter Sean O’Neill has described how his battle with cancer felt like a “double-edged sword” after it gave him time to nurture a scoop about alleged sexual exploitation by Oxfam aid workers and help other patients by exposing NHS restrictions on a new drug.

O’Neill was able to spend months on the story revealing some Oxfam staff had paid to use prostitutes while providing aid relief in earthquake-torn Haiti after taking a step back from “frontline news” when his cancer returned after a remission of more than five years, he told Press Gazette.

The story gained momentum worldwide after it was published in February, resulting in the resignations of top Oxfam staff and a nomination for the Private Eye Paul Foot Award for Investigative and Campaigning Journalism.

Soon afterwards O’Neill exposed restrictions on a drug which had been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence last year but limited by the NHS, after he himself was denied the drug and “stumbled into a story”.

O’Neill was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in 2010 and, after a course of chemotherapy, entered remission.

He said he knew developing the Oxfam story should be his focus when he took a step back from the “hectic helter-skelter” of the daily news agenda in September last year.

“I knew I was onto something there and that gave me time to develop that story and pursue it,” he said. “So in a way the disease is like a double-edged sword – it gave me the time to do it.

“Then when it broke, in that two to three-week period it was so busy and so frenetic the story became a runaway train almost and I didn’t have time to think about the illness really.”

Over the course of ten months, starting from a what he described as a “vague tip-off”, O’Neill slowly built up a picture of how Oxfam had mishandled allegations of sexual abuse by staff.

By nurturing sources he was able to run an initial story in October about a high-level Oxfam employee who claimed to have been sexually assaulted by a colleague.

The impact of the staff member’s story brought more sources forward and O’Neill eventually obtained Oxfam’s internal investigation report into the 2011 Haiti prostitution allegations.

A key breakthrough on the Oxfam story coincided with good news about O’Neill’s illness – that doctors believed there was no immediate need for treatment despite the cancer’s return, and that it may not be necessary for several years.

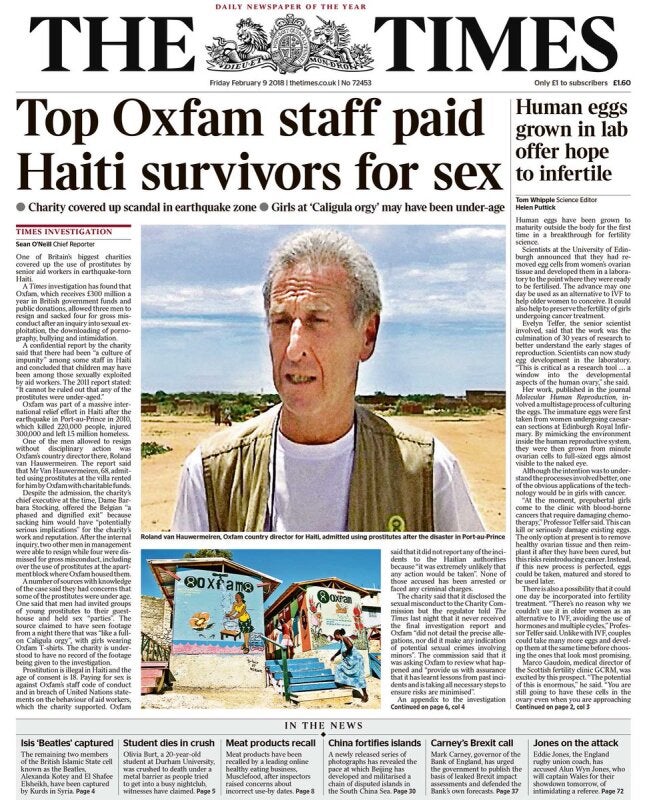

The scoop was published on 9 February under the front page headline: “Top Oxfam staff paid Haiti survivors for sex,” and quickly received a global response, with the Department for International Development pledging the same day to review its work with the charity.

Times front page 9 February: “Top Oxfam staff paid Haiti survivors for sex.”

The story claimed senior Oxfam official Roland Van Hauwermeiren had been named in the charity’s internal report as having admitted to paying for sex at a villa rented for him in Haiti using charitable funds.

He later told a Belgian newsaper that while “there are things correctly described” in reports he had also “read a lot of lies and exaggerations”.

The Times article resulted in the resignation of deputy chief executive Penny Lawrence, who said she was taking “full responsibility” for the behaviour of staff, as Oxfam’s ambassadors and partners began distancing themselves from the charity.

Months later Oxfam chief executive Mark Goldring announced he would step down at the end of the year following the “very public exposure of Oxfam’s past failings”.

But within weeks of publication, as the news cycle began to move on, O’Neill began noticing pain and discomfort in his lower back and stomach.

He was told in March that he would need treatment again within the next three months due to dangerously large and growing lymph nodes in his abdomen.

However he was told by his doctor he was not eligible for Ibrutinib, an inhibitor drug which blocks energy going to cancer cells, because he had been out of remission for more than three years – one of the restrictions imposed on its use by the NHS.

This meant potentially having to undergo chemotherapy again, which had previously weakened his immune system to the extent he contracted pneumonia eight months after finishing treatment.

O’Neill said his consultants were “clearly frustrated and angry” that they could not give him the best available treatment, and that he decided to “put his reporter’s hat on”.

He obtained the document revealing the NHS restrictions on Ibrutinib’s use and spoke to numerous doctors to get their thoughts on the drug’s efficacy.

“At some point on this little journey of discovery a consultant looked at me and said ‘somebody needs to make a stink about this and you’ve got a platform’,” O’Neill said.

“For me that was a moment where I thought ‘right, I’ve got to put myself in the glare’.

“What made the decision for me was I thought I’ve spent 30 plus years reporting and a lot of reporting is about asking people who are in pretty dire circumstances in their lives to speak publicly about things, whether it be because their relative has been murdered or they’ve been involved in some horrible disaster or they’ve survived a bombing.

“We’re constantly prying into people’s lives when they’re at extreme points in their lives and it was like right, this is my time to ask myself that question – are you going to talk about this? Can I stand up and step up and say this is what’s happening?”

He added: “I’d stumbled into a story and I was the case study.”

On 12 May O’Neill published his story – the most personal thing he has ever written “by a long way” – and it was teased on the front page of the Times under the headline: “My cancer drug battle.”

Times front page on 12 May 2018, including Sean O’Neill’s “My cancer drug battle”.

The Times subsequently published more comment pieces, with health editor Chris Smyth taking on some of the news reporting, while O’Neill spoke about his story on BBC Radio 2’s Jeremy Vine Show and was invited to write in the comment pages of the Telegraph.

The cause was taken up by a number of patient advocacy groups, including Bloodwise, Leukaemia Care and the CLL Support Association, and O’Neill believes it was ultimately the political pressure created by these organisations, alongside the “power of the press”, which led to a U-turn from the NHS, announced earlier this month.

Speaking of the result, O’Neill said: “I was delighted and quite emotional and overwhelmed by it, because it was personal in a way that no other story has been personal.”

He said he knew that he would be able to access the drug regardless due to his employer’s private healthcare scheme, but said it was “massive” for others in the same category as him, which he estimated at around 200 to 300 people a year.

He said he now wants to look into how many other drugs may have been approved for use by NICE but restricted by the NHS in similar circumstances.

By contrast, however, the Oxfam story has yet to find closure, according to O’Neill, who said it was “only really in its infancy”.

“It’s had a global impact in terms of publicity,” he said. “What I think we haven’t seen yet is – will it actually bring about lasting change?

“I think there is a recognition that there was a problem there. The Oxfam story exposed something that, as the [International Development] Select Committee said the other week, was an open secret in the humanitarian sector.

“They’re all talking about it, there’s all sorts of promises of reform, but frankly if you look back into the history of this problem there have been these promises of reform before.

“What we haven’t yet seen is concrete action and that means in terms of people not just having brilliant safeguarding policies but actually having really good enforcement of those policies and mechanisms for making them work around the world.”

Picture: Clara Molden/The Times

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog